Rayonier Foresters Build Plans Around Protecting Gopher Tortoises

Originally published on Rayonier.com

Foresters take their responsibility to guard protected species seriously. When it comes to the gopher tortoise, a keystone species whose burrow provides shelter to more than 300 other types of forest creatures, we build our planting and harvesting plan around ensuring their safety.

LONG COUNTY, Ga., August 9, 2023 /3BL/ - Blake McMichael stands on the boundary line between two Rayonier forests. He points out the differences between the one on his left, a forest with wet, clay soils, and his right, a dry, sandy forest that has been managed differently in order to protect gopher tortoises and their burrows.

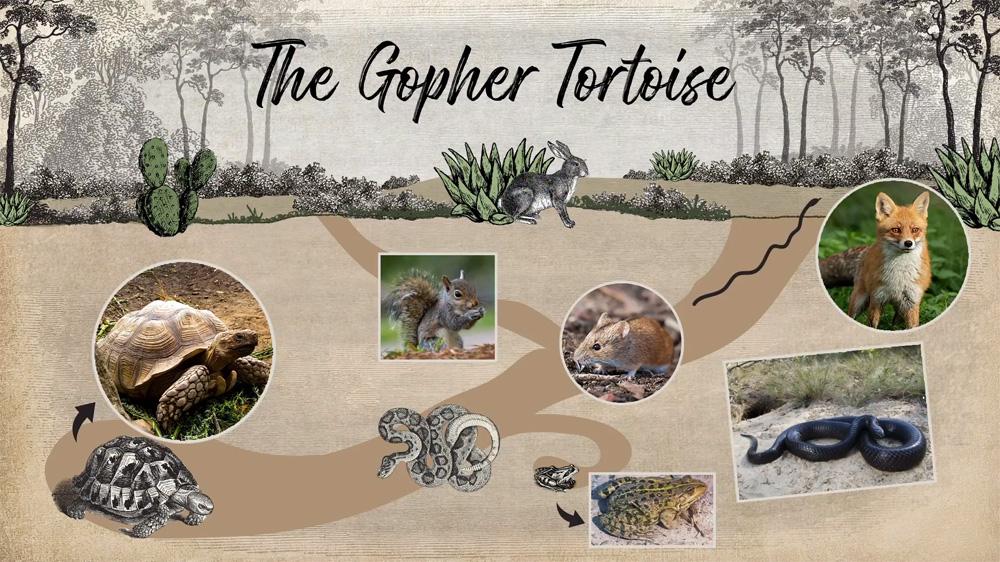

Preferring dry soils, gopher tortoises are what’s called a keystone species, so named because their burrows provide shelter to as many as 300 other types of creatures in the forest. Rabbits, mice, insects, birds, foxes and even snakes seek shelter in their burrows, including the federally-threatened Eastern Indigo Snake.

“By protecting burrows, we’re not only helping the gopher tortoise, but also the many other species that use its shelter,” Blake says.

Blake, a Resource Land Manager in charge of replanting forests, has the drier, sandy forests that are inhabited by gopher tortoises planted by hand. Minimizing the use of heavy equipment helps protect gopher tortoises and their burrows. The young trees will grow among vegetation like palmetto bushes and other undergrowth gophers like to eat.

On wetter soils nearby, where gopher tortoises don’t go, he had rows plowed and mechanically planted, encouraging much faster growth rates.

Found in the Southeastern U.S., gopher tortoises are vegetarians who eat berries, grasses, mushrooms and prickly pear cacti. They’re prolific diggers, with burrows reaching depths of 9 to 23 feet deep and 3 to 52 feet long! When they reach adulthood, they’re typically 15 inches long and weigh 8-15 lbs. Their average lifespan is 80 years.

Protecting Gopher Tortoises While Planting Trees

Rayonier has its own spatial mapping system, not unlike the GPS systems consumers use when they travel. Our system has many layers of information, including a property’s soil type, topography, what has been planted there previously, notes about any protected species on the property, and much more. All that information is available on a tablet foresters can take with them into the woods.

When Blake looks at a stand of trees in the system, he can quickly find out if it has the dry, sandy soils and higher ground that gopher tortoises prefer. If active burrows have been identified on the property previously, foresters leave “pins” on the map. These indicate the presence of gopher tortoises in that particular stand of trees.

Blake also walks through the forest to visually survey the site, checking for active burrows in the process. He looks for the characteristic oval-shaped hole in the ground with a wide, sandy collar (or apron) in front. An active burrow will have clean, smooth sand in front of it, while abandoned burrows may be overgrown. The average male tortoise may dig as many as 35 burrows in his lifetime.

Protecting Gopher Tortoises During a Timber Harvest

On the other side of our business, when forests are full grown and ready for harvest, we work with our logging contractors to protect gopher tortoises and their burrows. This may include site visits, pre-harvest meetings, flagging, and showing pictures to help them know what to look for.

If a burrow is in a location where it could be overlooked, our foresters find creative ways to ensure it’s safe. In one instance, when an active burrow was found right next to a forest road, a Georgia forester had a logger place a barrier of logs beside the burrow to ensure no one drove on top of it. In another instance, our forester directed a logging crew to cut a series of trees about 4 feet high to visually cordon off an area around a burrow.

“One of the most important things that we can do as foresters is to ensure that whoever is working on our properties can play a role in protecting the burrows while they’re on site,” Blake says.

Many Species Protected in Our Forests

Gopher tortoises are just one of a myriad of wildlife Rayonier protects on its land. For example, throughout the U.S., we protect the American Bald Eagle and its nest. In the Pacific Northwest, we protect Northern Spotted Owls and Marbled Murrelets. We have invested tens of millions of dollars into restoring salmon habitat in Washington State alone. We protect the habitat of the Red Hills Salamander in Alabama, and the Leopard Darter Fish in Oklahoma. In New Zealand, we work with conservation agencies to protect kiwi, New Zealand Falcons, and New Zealand Sea Lions. You can learn more about the many species we protect here.

And while we’re taking special care to protect vulnerable species, our forests are providing clean air, habitats for many other creatures, and clean water while they grow. Once grown, our trees will become the raw material needed for 1000s of everyday products, and we’ll replant the site for the next generation of trees.

“We’re providing a renewable, sustainable resource that people need,” Blake says. “We want to make sure we’re leaving areas where future generations have the animals that live on the property as well as the resources provided by the property.”