A Firefly's View of the Insect Apocalypse

Initiatives to Address Light-related Animal Welfare Challenges

NEW YORK, March 17, 2021, /3BL Media/ — The Zoological Lighting Institute™ (ZLI) recognizes the publication of an important new study enhancing growing awareness that light pollution is driving the insect apocalypse, a deadly global decline in insect populations that threatens food security and human sustainability in general. ZLI will dedicate a portion of its ZALA Animal Welfare Stations to monitoring artificial light in the environment, and to aid ongoing research efforts through grants, resources, and expertise provision.

This week, the Journal Insect Conservation and Diversity will dedicate a special issue focusing upon the role of light pollution in bringing about the ‘insect apocalypse’. This latest initiative builds upon the paper “Light Pollution is a Driver of Insect Declines” published in the journal Conservation Biology by ZLI Board Members Avalon Owens, Brett Seymoure, et. al., and championed by ZLI in 2019. Awareness is growing, though the issue is urgent.

As explored in the ZLI documentary Brilliant Darkness: Hotaru in the Night, light pollution outshines fireflies with dark consequences. Research undertaken at Tufts University suggests that the fireflies that light up our summer evenings are struggling to communicate under artificial illumination – and if we’re not careful, our lights will extinguish theirs forever. Many fireflies rely on a back-and-forth courtship dialog as a crucial prelude to mating. But when subjected to overhead lights, males flash halfheartedly and females rarely flash back. Unless we cut back on our outdoor lighting, fireflies might not light up our nights much longer.

Biologists at Tufts University reveal the results of over two years of laboratory studies, showing that, when illuminated by different colors of artificial light, fireflies don’t flash nearly as much as they do in darkness. White and amber light in particular cause female fireflies to go completely dark. “I was shocked,” says first author Avalon Owens. “This kind of thing could devastate a population, because fireflies use flashes to find and seduce each other. If they don’t flash, they don’t mate, and there is no next generation.”

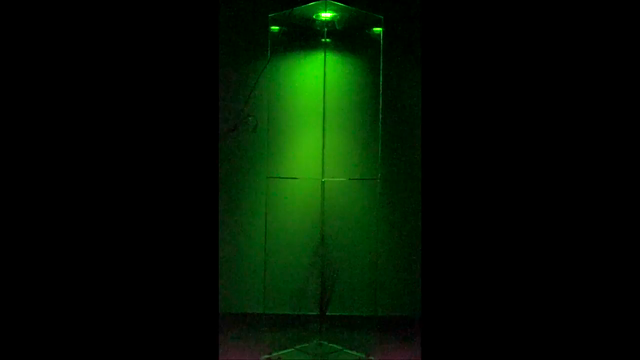

The authors investigated the impact of light pollution on firefly courtship by putting pairs of Photinus obscurellus fireflies in a dark chamber and watching them interact. Usually, males of this species emit around 10 flash patterns per minute, each flash pattern composed of three to four short bursts of light. The females waiting below enjoy the show, and flash back when they have decided to mate. “If the female never responds to the male’s advertisements, he basically has no idea where to find her,” explains senior author Dr. Sara Lewis. “The moment she does, he zips over – and that’s when the magic happens.”

To see how artificial light affects firefly courtship, the authors first filmed the fireflies in darkness, and then illuminated the room with one of five colors of LED light – cool white, warm white, blue, amber, and red. They hoped to find a color of light that people can see, but fireflies don’t mind. “For a long time there has been this idea that fireflies can’t see blue light, that people should bring blue flashlights on firefly walks so as not to disturb them,” notes Ms. Owens. “Meanwhile, other people think that amber or red is a better choice. But until now, no one had ever actually tested different colors to see which one is the most firefly-friendly – if any!”

So, what color is best? All colors of light suppressed male flash activity a little bit: when illuminated, males flashed around five times per minute, instead of their normal ten. But the females were much more sensitive: they responded about half as often under red and blue light, and hardly at all under cool white or warm white. What’s more, they never flashed even once under amber light. “It’s definitely concerning,” says Ms. Owens, “because many ecologically-minded people are turning to warm white or amber lights as a way of safely lighting up streets and parks. But what we’re finding is that no color of light is safe for firefly courtship.”

“Darkness will always be best for fireflies,” agrees Dr. Lewis. Both authors recommend minimizing artificial light sources around firefly habitats, and installing timers, motion detectors, or dimmers to further obscure the lights that are there. For more details, you can consult the Firefly-Friendly Lighting Practices guide put out as a collaboration between the authors and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Avalon Owens is a PhD candidate in biology at Tufts University, where she studies how light pollution affects fireflies and other insects. Sara Lewis, PhD is a professor of evolutionary ecology at Tufts University and author of Silent Sparks: The Wondrous World of Fireflies.

Press Contact: Stephen Villante, Communications, Avalon C.S. Owens, Author

Phone: 01.212.317.2927

E-mail: admin@zoolighting.org, avalon.owens@tufts.edu

Video Captions: An Experiment to Determine the Impact of Artificial Light on Firefly Reproduction" ©AvalonCelesteOwens and the latter BDHN as "Brilliant Darkness: Hotaru in the Night" ©TheZoologicalLightingInstitute

#####