Why Pathogen Surveillance Is Critical During a “Tripledemic”

On the heels of three new RSV vaccines, an Arizona State University viromics lab identifies many variants

Originally published on Illumina News Center

The 2022–23 “tripledemic” season—in which influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) all surged at the same time—was especially bad for Arizona, says Efrem Lim, an Arizona State University (ASU) virologist with the Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics at the Biodesign Institute. “What was really unusual with this tripledemic was that the RSV and flu season came about a month or two months earlier than when we typically see it. And the fact that they coincided created a very big burden on our health care system.”

One challenge during this tripledemic was accurately diagnosing a person with flu-like symptoms. Viral respiratory infections are especially easy to misdiagnose, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the problem. If an older adult with RSV is instead treated for influenza by mistake, this can delay appropriate care and risk their condition worsening, leading to unnecessary antibiotic use or inappropriately targeted antivirals, an extended hospital stay, and increased risk of spreading the infection to other vulnerable members of their family and community.

In May 2023, GSK and Pfizer released the first two FDA-approved RSV vaccines for adults 60 years and older. In August 2023, the FDA approved a Pfizer vaccine for pregnant people to protect infants at highest risk of mortality from RSV. “The vaccines are a big game-changer,” says Lim, an associate professor with the ASU School of Life Sciences. “This is a big deal. We’ve never ever had vaccines for RSV.”

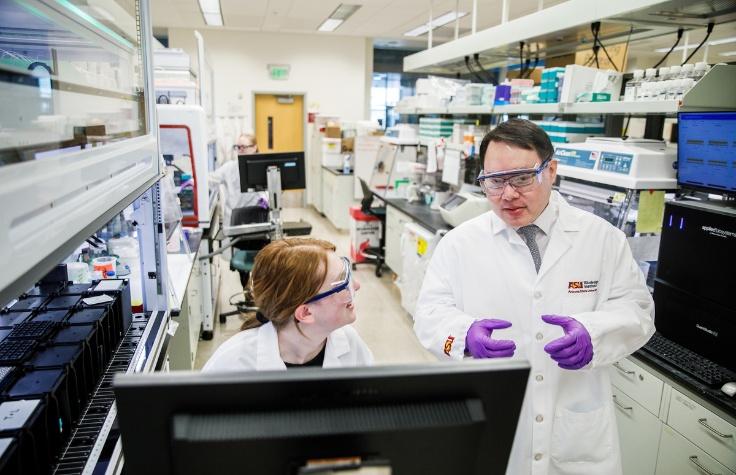

The Lim Lab is located on the ASU Tempe campus. The moderate-sized, CLIA-certified lab is equipped with two Illumina NextSeq 2000 instruments and employs genomics to study human viruses. It also sequences clinically relevant specimens from major hospitals in Maricopa County, where a majority of the state’s population resides, and reports results to the Arizona public health department and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These entities currently collect data on RSV-associated hospitalizations through the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance Program. Lim wants to raise community awareness about the RSV vaccine and emphasizes the important role of genomic surveillance—to make sure the vaccines are maintaining protection over time.

Lim and his team conducted a sequencing study of 100 RSV-A specimens and 27 RSV-B specimens from cases at Arizona hospitals during the height of the tripledemic, between November 2022 and April 2023.

Using the Illumina Respiratory Virus Oligo Panel (RVOP v2) hybrid capture, they achieved 100% genome coverage to a viral load of Ct < 33. “That’s the surprising thing,” Lim says. “Normally, it’s hard to get full genome coverage, particularly when a sample has a very low viral load. So, it’s very promising having this product’s increased sensitivity when you’re trying to get as much information from the virus as you can from every person that’s infected.”

The study team sequenced the samples to determine which subtypes of RSV were present and gain clues into how they were evolving and spreading. Next, they mapped those sequences onto the parts of the viral genome that would be targeted by the vaccine to see if there were mutations that could escape and cause problems. Specifically, they examined the parts of the viral genome that are predicted to be involved in exposure of surface proteins that interact with antibodies.

Discovering mutations

The RSV vaccines target the F protein antigenic sites of the virus. Lim explains: “For us, the best case would be that we didn’t find any mutations in the F protein, which means our vaccines are fine and should probably work. Unfortunately, in this case, we started seeing mutations already existing in these viruses in our communities.” He and his team found seven different mutations in RSV-A and five in RSV-B. It’s unclear whether those specific mutations will affect vaccine response. “This was not what I was expecting. Maybe one mutation, two mutations—not this many. But again, mutations happen naturally. Not all of them cause a problem. But we need to make sure we’re keeping up with our sequencing surveillance to catch anything and then update our vaccines accordingly.”

The team’s study, “Genomic Sequencing Surveillance and Antigenic Site Mutations of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Arizona, USA,” was published this month in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Lim says that to his knowledge, no one is routinely sequencing the RSV-positive samples circulating in the community. This is likely because no previous RSV vaccine had been available and because routine respiratory viral sequencing was uncommon before COVID-19. The availability of new vaccines changes the equation for molecular surveillance. The viruses that cause flu, COVID-19, and serious RSV disease are all prone to rapid changes in their genomes, so population-level sequencing is especially important for both the original design of new vaccines and for monitoring to make sure vaccines still “match” the strains that are causing the most disease.

Looking ahead, Lim is interested in expanding pathogen surveillance for public health. He tells his students to think not just about the viruses but about the applications and technologies available for public health surveillance.

“Everyone thinks that only doctors save lives, and I’m trying to tell them that researchers are an important part of the public health system as well. The things you do prevent outbreaks, and if you can improve a vaccine’s design, you can save many more lives in the future. It is what researchers do.”