U.S. Building Performance Standards in 2023 and Beyond

Building Performance Standards aim to mitigate climate change impacts and support building decarbonization, creating a more resilient built environment.

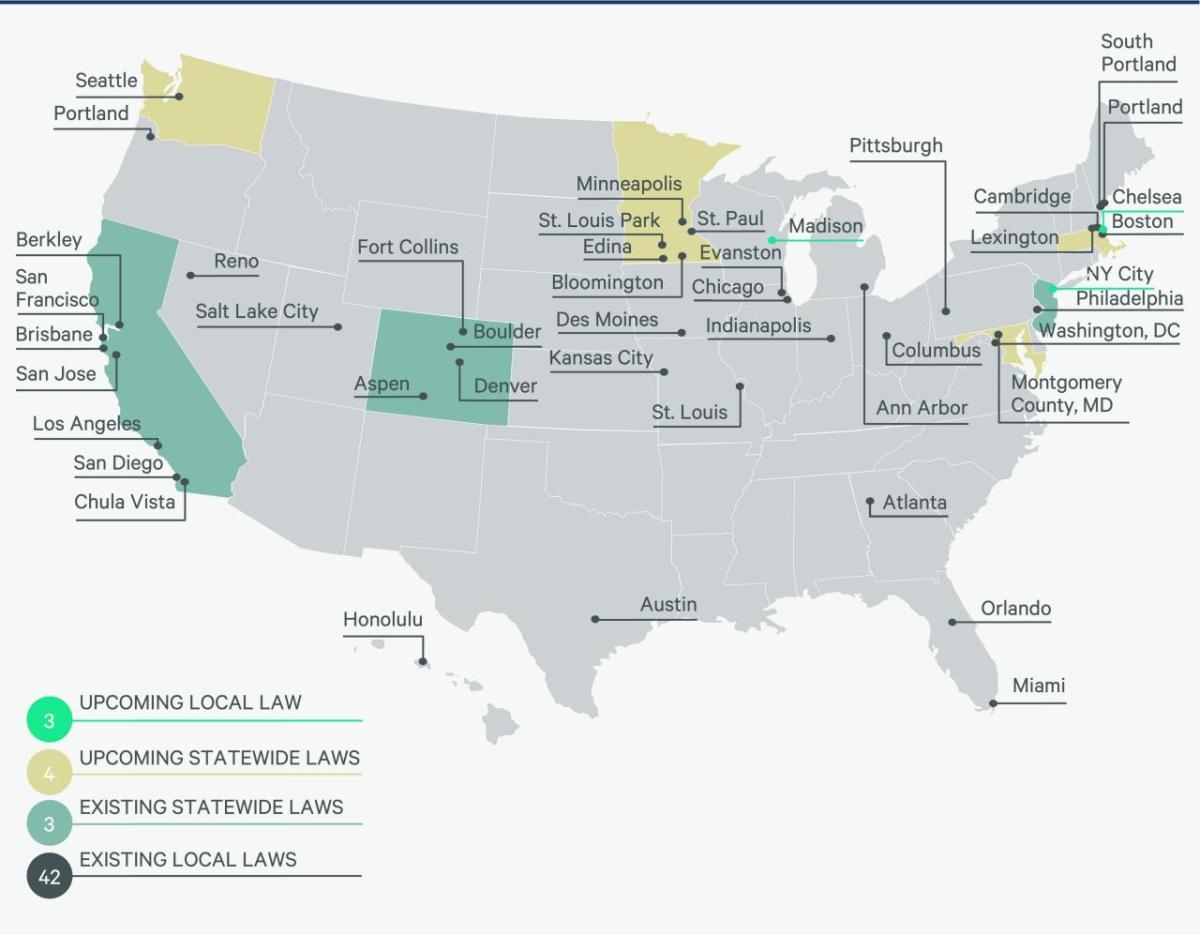

In November 2022, CBRE Econometric Advisors (CBRE EA) published a report outlining how local and state government mandatory regulations are aimed at combating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the real estate sector. Over the past decade, these mandatory Building Performance Standards (BPS) policies have gained momentum, as an increasing number of local jurisdictions act to mitigate climate change impacts and support building decarbonization. In 2023, 10 more local jurisdictions across the country joined the growing list of BPS implementation.

The adoption of statewide policies for BPS is also on the rise, reflecting the commitment of states to address climate change and foster sustainable practices on a broader scale. New Jersey joined California and Colorado in 2023. Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Washington are scheduled to do the same over the next three years. Statewide adoption ensures that compliance and community benefits will cover every corner of the state and not just cities. While Maryland’s statewide policy awaits implementation, some local legislators enacted the BPS policy at a countywide scale instead of within city limits. Montgomery County, MD, which is a suburb of Washington, D.C., is a primary example of such efforts.

Momentum is growing for a more collaborative approach

In January 2022, the federal government launched the National Building Performance Standards Coalition, a collective partnership between state and local governments to advance building performance legislation. The Coalition set a goal to implement building performance policies and programs by Earth Day 2024, with many jurisdictions already having existing policies in place. This growing momentum for the adoption of BPS throughout the United States suggests policy adoption is not slowing down anytime soon. Several cities have stipulated strict financial penalties for policy violations. The cumulative effect of such penalties will help encourage accountability and help accelerate decarbonization.

Penalties and their impact on commercial real estate

Penalties for non-compliance with BPS vary depending on the specific regulations in place. By implementing penalties, local authorities aim to create a level playing field for all market participants and incentivize building owners to invest in energy efficient and sustainability practices. However, it’s important to note that these penalties are intended to encourage building decarbonization rather than penalize building owners for failing to reduce the building’s energy consumption and carbon footprint. Some jurisdictions have relatively low annual penalties, whereas others have heavy penalties.

Another penalty is reputational through the public disclosure of non-compliant assets. Some jurisdictions will publicly disclose non-compliant buildings, which could negatively impact the reputation of the building owner or operator. In today’s society with growing stakeholder concerns about climate change1, investors, tenants, and regulators increasingly expect businesses to display their commitment to sustainability and demonstrate progress. Non-compliance with BPS can be seen as a lack of commitment to responsible business practices, leading to negative perceptions among stakeholders. Commercial tenants, especially those with corporate social responsibility and sustainability policies, prefer leasing spaces in energy efficient and low or zero carbon buildings2. Non-compliance could make it challenging to attract and retain such tenants, leading to higher vacancy rates and lower returns on investment.

Calculating non-compliance penalties

The penalties for non-compliance are designed to encourage asset owners to make all efforts necessary to decarbonize the built environment and comply with local regulatory policies. Avoiding penalties can reduce business expenses, which can be quite significant. While most jurisdictions impose annual fines on a per-day basis, three jurisdictions took a step further and base penalties on energy consumption over a 12-month period.

Following are examples of the potential impact on net operating income (NOI) in three jurisdictions — Denver, Boston, and New York City — that will impose financial penalties on properties that fail to meet carbon reduction mandates. Figure 2 outlines the calculations described for each city.

1 https://www.danpal.co.za/green-buildings-are-the-goal-for-the-future-of-construction

2 https://www.cbre.com/insights/viewpoints/the-case-for-esg-adoption

Denver

The City of Denver addresses climate change through regulations and programs aimed at improving the energy efficiency of existing commercial buildings. The local Energize Denver ordinance establishes Energy Use Intensity (EUI) targets for buildings 25,000 sq. ft. and larger; these buildings must meet a final EUI target by 2030, with interim targets in 2024 and 2027. If a facility exceeds the maximum allowed energy amount set for that building, it will incur a penalty of $0.30 for each kilo British thermal unit (kBtu)* reduction required per year that the asset owner fails to achieve in that interim period. The city also retains the authority to impose fines up to a maximum of $0.70 per kBtu. The highest potential penalty would be imposed on all property owners who have not made any efforts to achieve the 2030 targets of a 30% EUI reduction and maintained the same level of energy consumption throughout the interim periods. Figure 2 shows a hypothetical example of how this could potentially lower the building’s NOI due to excess use of energy, if the building did not receive the electrification credit, purchased, or installed renewables, and did not apply for one of the alternate compliance options.

Based on the latest data from CBRE EA, a typical 500,000 sq. ft. office building in Denver generates an average NOI of $5,180,000 in 2023. However, if such building exceeds the maximum allowed target by 1,000,000 kBtu, a penalty of $0.30/kBtu would be imposed, leading to a substantial 5.8% decrease in NOI.

* British thermal unit (Btu) is a measure of the heat content of fuels or energy sources. Energy, or heat content, can be used to compare energy sources or fuels on an equal basis. Fuels can be converted from physical units of measure (such as weight or volume) to a common unit of measurement of the energy or heat content of each fuel.

Boston

The Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO) is a significant sustainability-focused initiative enacted by the City of Boston. The city’s goal is to gradually reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2050. The ordinance requires the owners of all commercial properties 20,000 sq. ft. and larger to report their energy and water usage annually through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager platform, the industry’s standard benchmarking reporting tool that allows asset owners to compare their building’s energy usage with similar buildings on the market or industry standards. Penalties for failure to comply with benchmarking requirements and standards will be assessed annually, ranging from $300 to $1,000 per day. Additionally, asset owners will have the option to make Alternative Compliance Payments (ACP), a form of carbon offset measure, to mitigate residual GHG emissions. The ACP fee is set at $234 per metric ton of carbon equivalent (tCO2e/year) per year and is subject to change every five years. ACP allows building owners to tailor their compliance strategy to their unique circumstances, which in turn will not decrease the building’s NOI as drastically as per-day penalties. As per the most recent research by CBRE EA, an average office building of 500,000 sq. ft. in Boston yields an annual NOI of approximately $9,705,000, and potential penalties could reduce NOI by 5.1%.

New York City

New York City’s Local Law 97 (LL97) will assess penalties in a similar manner to Boston but with a slight twist. All commercial buildings 25,000 sq. ft. or larger should comply with LL97 starting in 2024. The city’s goal is to reduce GHG emissions produced by NYC’s commercial buildings by 40% by 2030 and by 80% by 2050. If a building exceeds its annual GHG emissions limits, the building owner will face the following financial penalties split into three categories: $268 per tCO2e/year over the building’s annual carbon emissions limit, $0.50 per building sq. ft. per month for failure to file report on time, and $500,000 for providing false statements.

To accurately calculate GHG emissions and the potential penalties, the authorities of New York City have issued a comprehensive advisory on emission factors. During the regulatory period from 2024 to 2029, the emissions factor3 for grid electricity stands at 0.000288962 tCO2e per kilowatt-hour (kWh). However, the emissions factor undergoes a notable reduction to a mere 0.000145 tCO2e per kWh for the subsequent period spanning from 2030 to 2034, making electrification the most cost-efficient option for the asset owners. This reduction diminishes the volume of GHG emitted per relevant time period and the potential fines associated with exceeding the emissions limit. Currently, buildings in New York City that surpass the GHG threshold will incur an annual financial penalty of $268 per tCO2e/year over the limit. Based on the figures provided by CBRE EA, the potential penalty for a 500,000 sq. ft. office property will decrease the building’s annual NOI by 5.6%4.

3 An emission factor is a coefficient which allows to convert activity data into GHG emissions. It is the average emission rate of a given source, relative to units of activity or process/processes. A coefficient is a numerical value that quantifies the relationships between different variables or factors in a mathematical or scientific context. It provides info about how one variable changes in relation to changes in another variable.

4 This number could go as high as 10.0% if the asset owner fails to file report on time and provides false statements. The $500,000 penalty for false statements is subject to change. The NYC Department of Buildings will conduct a public hearing in late October 2023 to amend this clause and introduce a new set of penalties. Under the proposed rules, building owners will be exempt from substantial fines and eligible for a two-year extension if they display Good Faith Efforts during the 2024-2029 compliance period and show progress toward meeting the city’s carbon emissions standards.

Aligning with BPS

Green Lease Clauses

Under a traditional lease agreement, clauses to support energy efficiency and other decarbonization measures (e.g., offsite or onsite solar, electrification etc.) are not typically included. With traditional leases, there is a “split incentive” challenge. This means, for example, in a triple net lease structure, the landlord is not incentivized to invest in measures that pay back over time through operational cost savings, because the tenant pays for the operational costs. Yet these are the very investments that will help support compliance with BPS. So, in a triple net lease structure, the landlord faces potential BPS financial penalties due to a tenant’s profligate energy consumption. This scenario creates a barrier that hinders both parties from prioritizing energy efficiency.

In a full-service gross lease structure, all expenses associated with building operations, including the burden of complying with decarbonization measures, also rest on the shoulders of the property owner. However, landlords, genuinely dedicated to green initiatives and those who have invested in energy-efficient building systems may be more inclined to offer incentives to tenants who share their vision. Tenants willing to commit to longer lease terms can gain more negotiating leverage when requesting concessions related to green lease clauses. These concessions may involve reduced rent or less aggressive rent escalations for tenants committed to sustainable practices. Additional incentives might include higher than usual tenant improvements and extended periods of free rent. While lease negotiations can be quite complex, it’s clear that they are a crucial starting point for achieving decarbonization goals.

To ensure tenant and landlord alignment, the parties can collaborate on adding green lease clauses to bridge this gap and provide a forward-looking solution. These clauses go beyond traditional lease terms by outlining specific obligations and commitments related to various sustainability measures, including energy efficiency, renewable power procurement, water consumption, waste management, and more. Such clauses can specifically address cost-sharing measures, for example, enabling a landlord to invest in measures that result in improved energy efficiency, reduced carbon, and operational cost savings. It can also include clauses around submeters and tracking of energy use and reward tenants who reduce their energy usage.

By incorporating green lease clauses, the goal is to align the interest of landlords and tenants, encouraging them to work together toward sustainable, lower-carbon and energy-efficient building operations. This shared responsibility fosters a collaborative approach, allowing both parties to contribute to a sustainable future by reducing carbon footprints and conserving resources. In this connection, it’s noteworthy that, according to CBRE’s 2023 Strengthening Value Through ESG survey, 36% of respondents in the U.S. said they would consider paying a premium for green lease clauses to enforce action.

Submetering

Every day, the need to reduce carbon emissions in the building sector becomes more pressing. Enhancing the efficiency of existing buildings through retrofitting is a high-impact method to decrease energy usage and move toward net zero goals. It is also a great way to comply with BPS and avoid hefty non-compliance penalties increasingly imposed by local municipalities. Prior to initiating any energy use enhancement endeavor, ensure that the building’s performance data is easily accessible through submetering, which enables the measuring and monitoring of individual tenants' energy consumption and bills them accordingly.

Additionally, submetering can be utilized to detect disparities in energy use and pinpoint opportunities for significant savings. Furthermore, submetering allows for monitoring of the large electrical equipment, such as HVAC, lighting and building automation systems, enabling facility management to proactively address any issues that may arise.

Applying submetering to the building with multiple tenants can lead to energy savings of up to 15%5. However, the actual amount of energy savings can vary based on several factors, including the specific metering architecture installed and the characteristics of the building, such as its size, type, and spaces. It is worth noting that although submetering can contribute to energy savings, its impact is just one aspect of an overall energy management strategy. To maximize benefits, it is essential to combine submetering with other energy efficiency measures, such as equipment upgrades, energy audits, and tenants’ behavioral changes.

Looking ahead

BPS policies are here to stay, and the penalties for non-compliance are likely to increase, just as the costs for climate change impacts are expected to rise without implementing mitigation and adaptation strategies. As the illustrative examples for Denver, Boston and New York show, the financial impact of BPS penalties can be significant for building owners. At the same time, there is an upside to meeting tenant and other stakeholder expectations through the implementation of BPS measures. Thus, the sooner both owners and occupiers unite on their sustainability efforts, the greater the combined impact will be. Shared responsibility for sustainable and energy-efficient building operations is not only essential but also a key to achieving long-term success in creating a more resilient built environment.