Tsunami Evacuation Shelters: Solutions for At-Risk Communities in Developing Nations

By: Angelos Findikakis, Senior Principal Engineer and Bechtel Fellow

Tsunami Evacuation Shelters: Solutions for At-Risk Communities in Developing Na…

Guest Authors: Tarek Elkhoraibi

Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

As part of Bechtel’s commitment to contribute 100 ideas to support the United Nation’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we examine the opportunity of providing shelter for developing countries susceptible to natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis for Petite Anse – a highly vulnerable community in Haiti.

11B. By 2020, substantially increase the number of cities and human settlements adopting and implementing integrated policies and plans towards inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation and adaptation to climate change, resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, holistic disaster risk management at all levels.

Challenge

In many developing countries, crowded conglomerations of low-rise houses have overgrown in flat areas adjacent to the ocean, with no higher ground to which residents can escape in the event of a tsunami. Large tsunamis caused by thrust earthquakes of magnitude greater than eight along subduction zones can devastate coastal communities and cause the loss of thousands of lives. Examples include the tsunami caused by the 2004 earthquake along the west coast of Sumatra that caused nearly 230,000 deaths, and the tsunami triggered by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan that killed over 19,000 people and damaged the Fukushima nuclear station.

The Caribbean is a seismically active area, especially the Eastern Caribbean, where the North American plate dips beneath the Caribbean plate and is prone to significant seismic hazards. The most recent reminder of these hazards was the January 2010 earthquake that resulted in more than 200,000 deaths in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The earthquake was caused by a strike-slip motion along the active Enriquillo fault system, a type of earthquake that normally does not create a tsunami.

Tsunami hazards are significant along the north coast of Haiti primarily because of the offshore North Hispaniola thrust fault. Experts estimate that the rupture of this fault could cause wave heights up to 10 meters offshore, and maximum wave height of up to 5 meters along parts of the shoreline, with flooding extending a few kilometers inland over adjacent low-lying coastal areas. The estimated arrival of the first wave triggered by such an event would be only about 10 to 15 minutes after ground-shaking.

Cap Haitien, the second largest city in Haiti, would be especially susceptible if this fault ruptures. Based on 2015 data, the city is home to about 275,000 people, 98,000 of whom live in Petite Anse, a low-lying, high-density community extending all the way to the shoreline with many houses right on the water (Figure 1). Simulations suggest the entire community of Petite Anse would be completely flooded in such an event.

Solution

In such disaster-prone areas, elevated evacuation shelters can be an integral part of a national or local disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategy and programs. They enable vulnerable communities to get to safety at the first warning of an incoming tsunami.

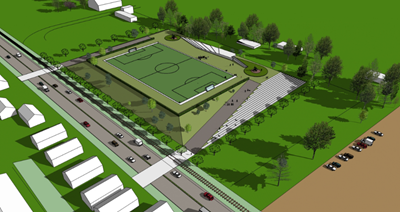

In the event of a tsunami, elevated shelters could help improve the safety of the Petite Anse residents. Most tsunami evacuation shelters around the world are multi-story buildings. Such shelters do not seem feasible in densely populated, high poverty communities like Petite Anse because of their cost and the relatively small number of people they can accommodate. The NGO GeoHazards International (GHI), has developed the concept of an elevated Vertical Evacuation Park (VEP) that was first proposed in Padang, Sumatra (Figure 2).

Approach

An elevated park would be higher than the maximum estimated wave height, could be repurposed for recreational activities, and may serve as an evacuation shelter in the event of an earthquake. A park with the dimensions of a standard soccer field would accommodate nearly 20,000 people. Stairs and ramps on all sides of the park would provide access for evacuees, including persons with disabilities.

A team of Bechtel and GHI experts met with stakeholders and visited sites to better understand the optimal siting for an elevated park shelter. The sites included an existing soccer field and several empty lots belonging to the city, so the construction of the shelter would not require the displacement of any residents. Ensuring the safe evacuation of the entire community of Petite Anse would require the construction of more than one elevated park and possibly larger than a standard soccer field.

Successful implementation of a tsunami evacuation program would include proper maintenance of the elevated park(s) ensuring that no objects block the available space and that the access stairs and ramps remain in good condition. In addition, regular public education campaigns would be needed to inform all residents that as soon as they feel strong shaking, they should move to the shelter as fast as possible. Education would also be required on the logistics of getting to the shelter and the importance of maintaining it as a public good.

Among the key steps necessary for the development of the shelters at Petite Anse are:

- formalizing the commitment of the national and local governments to the project

- gaining support in the impacted communities, selecting a site for a prototype shelter

- analyzing traffic and logistics

- conducting a health and safety assessment

- producing a preliminary design and a cost estimate for the prototype shelter

- designing and building the prototype shelter

Conclusions

Elevated shelters can be integral to a broader DRR strategy and plan by improving community resilience and protecting people and assets in vulnerable communities, particularly in developing countries. They are part of a multiple defense approach that combines modeling of historical and other potential tsunami events, consideration of local socio-economic issues and characteristics, and structural (e.g. seawalls and breakwaters) and non-structural measures (e.g. mangroves and forests).

Read the Bechtel blog for more.