The Secret Album Reveals How a Powerful Truth Changed a Family Forever

A novelist learns about her mother’s long-held secret by searching for what’s missing from her family photo albums.

Originally posted on Garage by HP

The Secret Album is part of HP's original documentary project, History of Memory, which celebrates the power of printed photos. Visit History of Memory to see more.

We treasure family photos not only because they illuminate the past, but also because they can offer up an alternative narrative to the stories we tell — and retell — about our identities.

This is true for author Gail Lukasik, who was just as captivated by what was left out of her parents’ snapshots as by the faces and stories they portrayed. Growing up in suburban Ohio, Lukasik puzzled over why there were so few pictures of her mother’s side of the family. In the stack of family photo albums, there were only a handful of black-and-white prints of relatives from New Orleans, where her mother, Alvera (Frederic) Kalina, had lived in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. “I felt very close to my mother, but she had a certain mystery,” she says. “When I used to ask her about that she’d say, ‘Oh I just don’t have any,’ which I thought was strange.” Her mother’s guardedness about her own family’s origins were yet another layer to their already complex relationship.

“I'll tell you one thing,” she says in The Secret Album, a new short film directed by Sarah Klein and Tom Mason for the Garage by HP’s History of Memory project about how printed photographs are sentinels of family history. “If your family has been in this country a long time, there's some secrets in your closet that you don't know about.”

Raised in an all-white, working class suburb of Cleveland, Lukasik had never thought of her parents, who described their ancestry as German and Bohemian on her father’s side and French and Scottish on her mother’s side, as anything but Caucasian. As a young adult, Lukasik set out to fill in the gaps in the family album by researching her genealogy — and what she discovered rocked not only her relationship with her mother, but also her fundamental sense of identity. While combing through microfilm records at the local library, she found that her maternal grandfather, Azemar Frederic of New Orleans, was classified as Black in the 1900 U.S. Census. “That was an out-of-body experience,” says Lukasik.

The Secret Album delves into the aftermath of Lukasik’s discovery that her mixed-race mother had spent more than half of her life “passing” as white after marrying her father, an Army soldier on liberty in New Orleans. With him, she moved to the North — one of an unknown number of people of African descent with light skin to have made the decision to live free from the restrictions and prejudice inflicted on people of color in this country. Lukasik longed to know: Why did she do it? What was the life that she left behind like in the intensely racist South during the Jim Crow era? And did her husband, who harbored his own, less strident racism, know her true identity?

It took Lukasik two years to confront her mother, and the encounter didn’t go well. “I had never seen her so afraid,” says Lukasik, who tells the story in her memoir, White Like Her: My Family’s Story of Race and Racial Passing. “She said, ‘Promise me you won’t tell anyone until after I die.’”

Reluctantly, Lukasik agreed to enter into a bond of secrecy with her mother, who never brought up the topic again. For 17 years, until after Alvera’s death in 2014, Lukasik never spoke of her mother’s true racial identity either to her or anyone else.

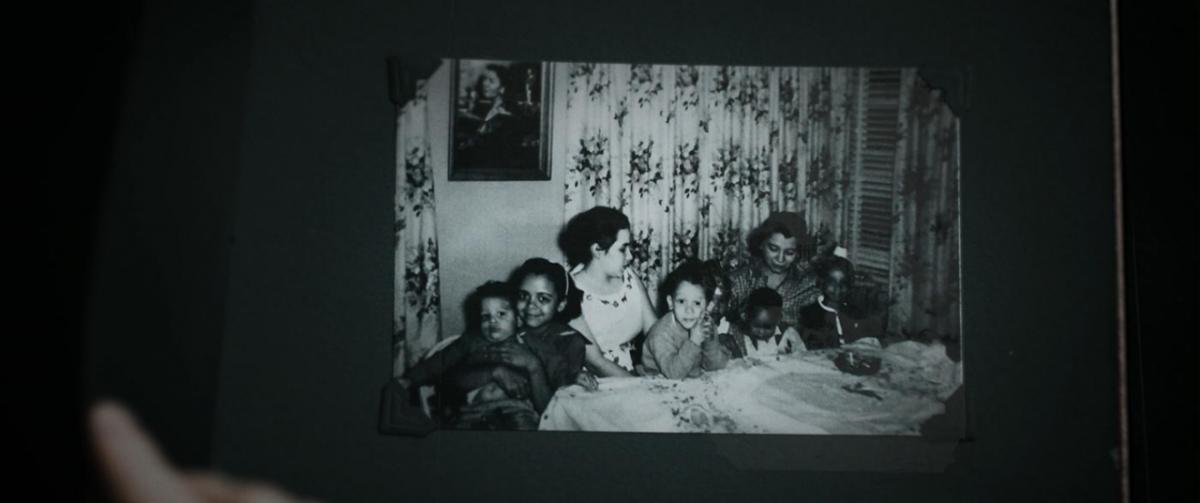

However, several years before her death, Alvera surprised her daughter with a well-worn photo album that she had kept hidden from her husband, now deceased, and her daughter for half a century. It contained page after page of photos of her life in New Orleans, her friends and family, her summer outings and carefree celebrations.

Lukasik was moved, and saddened, by what she saw inside. “I realized for the first time the depth of my mother's story of passing, from a life in New Orleans as a woman of color and then this tremendous shift in identity to move north and live as a white woman,” she says. She thought of how difficult that must have been for her mother, and how desperately she must have wanted to escape the crushing racism of the time and place she was born into. “She had to give up her family. She had to give up her authentic self, who she really was.”

For the filmmakers, the pivotal role that printed pictures played in Lukasik’s journey of personal discovery makes the story compelling to everybody who has ever immersed themselves in the family album in search of clues about who they are and how they got here.

“The fact that her incredible discovery began with the absence of a picture just made it seem all the more compelling to us,” says Klein. “Gail never got the chance to tell her mother how sad she is that Alvera felt she had to live a life pretending to be something other than who she was. And it strikes me as one of those profound sacrifices a mother can make for her children.”

DISCOVER: More stories of people whose lives were changed by printed photographs. Visit the History of Memory project.

WATCH: At First Sight, and see how a photo sparked a love connection across continents.