Knowledge without Borders: Reflecting on a Decade of Intellectual Philanthropy

By John Mendesh and Peter Erickson

Originally published by Cereal Foods World

In 2008, former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan and then General Mills CEO Ken Powell had a pivotal encounter at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, during which they lamented the intractable, intertwined problems of food insecurity and poor nutrition in Africa. Annan put a pointed challenge to Powell: find a way for General Mills to be part of the solution.

With Powell’s support, General Mills took up the challenge. Joined by Jeff Dykstra, a colleague and friend working in development in Zambia, we traveled across eastern and southern Africa looking at issues and opportunities across the food value chain to determine how and where General Mills might best offer assistance.

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to nearly half of the world’s fertile yet uncultivated land. Despite its agricultural potential, the region imports some US$35 billion in food every year, and one-third of the food that is produced locally goes to waste because of inadequate postharvest storage and processing capacity.

Through our travels, we realized that the highly specialized knowledge and experience of a company like General Mills could best be applied downstream in the local food value chain, in the processing sector. At a bar in Nairobi, we sketched out a simple model that is still followed today: a volunteer program for food technology professionals through which they can share their expertise with Africa’s most promising food entrepreneurs.

A little over a decade later 1,600 corporate volunteers have contributed more 100,000°hours to assist and train more than 1,500 early-stage food companies in Africa (more than one-quarter of which are owned or managed by women) to improve food safety, packaging, processing, marketing, and more. The program has helped client companies produce more than 1 billion meal equivalents (mobilizing US$26 million in finances), working with 1.4 million smallholder farmers in their supply chains, and helped put 87 new nutritious products on the market.

Brainstorming in that Kenyan bar, we never imagined that Partners in Food Solutions (PFS) would grow to become the unique and dynamic organization that it is today. Reflecting on the evolution of the program, we can pinpoint key learnings that have contributed to our growth—missteps, happy accidents, and smart decisions included—which we will discuss in this article.

Harnessing Knowledge

Intellectual philanthropy became the organizing principle of PFS and another step forward in corporate social responsibility for General Mills, where approximately 80% of the employees have contributed their time in the service of local charitable institutions, in addition to the company’s considerable financial donations. From the beginning, volunteers have worked remotely from anywhere in the world, collaborating with local African food businesses on specific, time-bound projects driven by their most pressing needs or challenges, whether developing new products, improving production efficiencies, or ensuring food safety. These experts devote 1 or 2 hours each week to participate in calls, review blueprints and flow charts, and share their knowledge.

Early in the development of the program, we began working with TechnoServe, a nonprofit organization that is addressing poverty through business-oriented solutions, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). TechnoServe provided local staff, food technologists, and business analysts to help facilitate the transfer of expertise from corporate volunteers to clients, leveraging key on-the-ground staff we began referring to as “translators” (now called program managers) who articulate client needs to volunteers and then assist in implementing their recommendations in operational plans. USAID provided funding, support, and local networking connections to make the new model work and still supports our work today.

After 3 years in development as an internal program, it was spun out as an independent nonprofit organization—Partners in Food Solutions. Since then, five other world-class food and agriculture companies have joined the PFS program: Cargill, DSM, Bühler, The Hershey Company, and Ardent Mills.

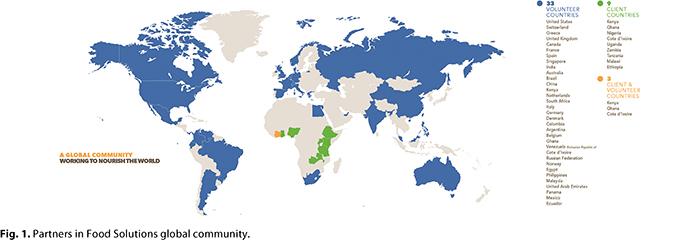

From the start, PFS has been rooted in relationships nurtured through a mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge. Individual relationships have led to organizational relationships that have grown into a multifaceted network of individuals, companies, governments, nonprofit organizations, and donors that now spans the globe. Today, we are all working together toward shared goals of improved access to safe, nutritious, affordable food and promoting sustainable economic development across food value chains (Fig. 1).

We have stumbled forward at times, but in the process learned valuable lessons that have helped to shape the PFS model, harness the expertise of food technologists, and catalyze the human ingenuity and entrepreneurial spirit of our clients. Intellectual capital is arguably the most important asset of any food company, and the same is true for PFS. Although many of our clients face challenges associated with accessing technology, equipment, and ingredients, it is the transfer of knowledge of best practices by our volunteers that truly drives the beneficial impact we see reflected in our clients’ businesses. There is limited leveraging of hard currency, but potentially infinite leveraging of wisdom and expertise.

A Client-Centered Model

Two primary groups are the heart and soul of the PFS collaboration—the food company clients across Africa and the volunteers from our six corporate partners. The current roster of volunteers includes nearly 1,600 experts. The volunteers are able to do most of their work remotely, thereby eliminating the time and costs associated with travel, which are natural barriers to scale.

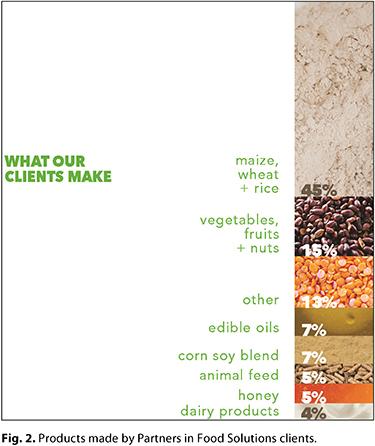

By working through partners who are in place on the ground, PFS ensures that its activities are locally owned and driven (Fig. 2). TechnoServe provides PFS with in-depth knowledge of a country and agribusiness expertise. This includes screening and identifying businesses with high potential for success and social impact, developing a detailed scope of the work to be provided by volunteers, and evaluating the success of each project.

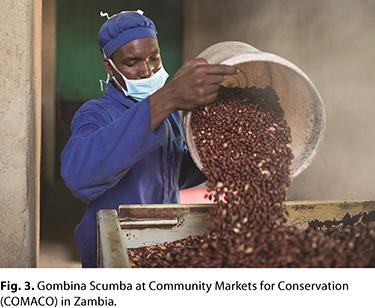

Often the most successful PFS clients are those who are able to find an untapped opportunity in a difficult challenge. One of our earliest and longest tenured clients, Community Markets for Conservation (COMACO), found a socially and environmentally sound business solution to the tensions and competition for resources between wildlife and smallholder farmers in eastern Zambia.

COMACO works with wildlife poachers, providing training in alternative livelihood skills, and with small-scale farmers, providing training in climate-smart, sustainable agriculture (Fig. 3). It then buys the farmers’ crops at a premium and turns them into nutritious, high-value food products that are sold under the brand It’s Wild! Through dramatically improved incomes and increased food security, COMACO’s 176,000 farmers—likely the largest farming collective on the African continent—have become stewards of their land and advocates for wildlife conservation.

A decade ago COMACO was beginning to explore how it could create value-added products, while General Mills was beginning to explore how it could make a positive social impact in Africa. COMACO became one of six pilot projects to test the new idea of tapping the expertise of highly trained food scientists to assist small- and medium-sized food processors on the continent. Together, PFS and COMACO teamed up to develop Zambia’s first manufactured breakfast cereal (Yummy Soy)—a product that is still thriving in the market today. PFS volunteers have worked on a number of other important projects since then, including consulting on the floor plan of COMACO’s processing plant, advising on a food safety lab, and sourcing secondhand food safety equipment to fully equip the lab.

The rates of deforestation in the valley have slowed, wildlife populations are rebounding, maize (corn) yields have doubled, and household food security levels are up 78%. COMACO sees all of this as proof that people are willing to stop poaching wildlife and other destructive behaviors if they are provided with economically viable, sustainable alternatives. PFS volunteers, in turn, are proof that people who are willing to share their knowledge can make a positive impact from half a world away.

Stumbling Forward through Failures

Just as client companies like COMACO do not become overnight successes, PFS too has had missteps that, looking back, rank among some of our most valuable lessons. We often say that we stumbled forward in the beginning, driven by passion and acting on faith. A few examples of our more valuable lessons learned through failure are described.

Devaluing the Freebie. We learned early on that people often do not value what they get for free, and as we generously offered our expertise for free, some clients reacted in ways we did not expect. For example, clients did not feel bad if they did not adopt advice or solutions in a timely fashion, much to the disappointment of our volunteers. Clients were often skeptical about our motivations, not trusting or believing that a world-class food company would give away expertise, even sometimes thinking we wanted to steal their businesses.

One way PFS has found to create a stake or sense of payment for our contributions has been to put a “pay it forward” clause in our agreements with clients, asking them for referrals to other company leaders in their network as a condition of working with them. We also have learned the importance of building trust and rapport with our clients. This can take more time up front, but generally leads to more sustainable outcomes.

Pull, Don’t Push. PFS also learned that our model relies on the client “pulling” toward a solution. We are not in the business of pushing solutions on a client. We try to listen to our clients more than we talk and remain humble, since we are coming in as outsiders to their cultures and businesses.

Without clients having a stake in the effort to develop a solution, or without taking the time to fully educate clients about our intent and building strong relationships from the beginning, our efforts to make a positive impact become more difficult.

All Clients Are Not Created Equal. We also made the mistake early on of assuming all clients come from an equal footing. We made a lot of erroneous assumptions. For example, in our early days working with COMACO, the company wanted a way to ensure peanut butter jars could show evidence of tampering. We recommended placing a plastic band around the lid after filling. When we received pictures of how they implemented the advice, we saw pictures not of an “around” but of an “over the top and bottom” application!

We learned from this experience never to take for granted that our recommendations will be received as intended and the importance of having the right “receiver” of our recommendations on the other end of the process who can implement our recommendations as the “sender.” Shortly thereafter, COMACO hired its first technical staff member. We have since collaborated on more than 50 projects with the company, working closely with its growing cadre of technical staff.

An Evolving Recipe for Success

The PFS model continues to evolve, but after a decade of working with this experiment, we have codified a winning recipe for scaling a sustainable positive impact with the entrepreneurs we support.

Building a Scalable Model. Most international volunteer programs are limited by the time and financial constraints of flying volunteers away from their posts. By leveraging technology to provide technical assistance remotely, PFS can enlist many more volunteers to serve many more clients for longer term engagements. This, in turn, makes it easier to volunteer, because the model only requires a volunteer to find a few hours during their workweek to engage with their clients. The key to the model is having “translators” on the ground locally and in a position between the client and volunteer to lay the pre-engagement groundwork and perform important follow-up tasks after an assignment has been completed.

Getting to the Right Problem Is as Important as the Solution. Our on-the-ground program managers work to find the right clients and then ask them the right questions to identify well-defined challenges that PFS can help them solve. They put together problem statements that become the roadmaps volunteers can use to navigate solutions with clients. Without this, our work is very difficult, and volunteers risk focusing on the wrong issues. Sometimes clients will start out wanting a business plan without articulating the pressing need for it; we keep our engagements grounded in what a client needs today and what they have to work with to accomplish their goals. For example, there is no point in seeking HAACP certification if the windows in your processing facility do not yet have screens.

Connecting the Dots. We learned from General Mills’ open innovation experience the importance of being great “dot connectors,” rather than “dot collectors.” When solving a challenging technical or business problem, leveraging the experience and expertise of multiple individuals from multiple companies brings a richness and diversity of thinking and capabilities that can unlock novel solutions. At PFS we have seen that bringing together experts from diverse companies and perspectives to work on a client’s problem greatly enhances the quality of the solution.

Fostering Enduring Relationships. PFS also has discovered the value of building relationships that last, with our clients, volunteers, corporate partners, and implementing partners. The synergies and shortcuts that happen because we have developed deep working relationships yield daily dividends for all of our stakeholders.

However, another lesson from General Mills’ philosophy of open innovation that has been leveraged by PFS is to work hard to ensure that regardless of when, why, and how a relationship with a client ends, that it ends positively. You never know where the road ahead will lead, and having built many positive relationships is always a good thing.

Right-Sizing the Elements. The PFS model is unique and requires that we keep all “legs of the table” balanced. In short, we need to balance retaining the right number of clients, the right number of volunteers, the right scope of activities asked of our field program managers, and the right amount of accessible, affordable capital for our clients.

Each of these elements is critical, and they all work together in maximizing impact. We have learned that if any one leg is off balance, the whole table wobbles.

Selecting High-Potential Clients. With limited financial, human, and technical resources, it is crucial to select motivated clients who have the most potential to maximize the impact of the proposed project. PFS has a simple yet powerful checklist it uses to evaluate the potential of every prospective new client. At the very top of the list is the presence of ethical leadership. Without the right leaders espousing strong values and a commitment to doing the right thing, we know that our efforts to assist will have little chance to be sustainable. The next must-haves on the list include access to capital, technical staff, and a commitment to “pull” the client toward a solution (again, drawing from our early lessons), which ensures the client will be able to take advantage of recommendations and expertise offered by PFS. We also look for at least three of four other criteria: potential for US$1 million or more in sales; a focus on affordable, safe, and nutritious foods; a presence in an appropriate value chain where PFS can contribute expertise; and a desire to build community. In short, we seek clients who not only have good business potential but also have high potential for a positive social impact.

This due diligence helps ensure PFS can gain the greatest benefit from the knowledge of our volunteers by choosing the most appropriate clients. We have found that if our clients are too small (using annual sales as a proxy), they are not as likely to implement a solution.

Prioritizing and selecting clients with the highest potential does not mean PFS will walk away from a small company in need of help, however. For those companies that are too small for direct intervention, PFS offers sector-wide training opportunities on basic topics to help get them started.

Power of Partnerships

Partnerships are one of PFS’s super powers, bringing together different types of partners has allowed PFS to do more than any of us could do alone. Building and scaling multisector partnerships among some of the world’s largest food companies, some of whom are business competitors, was one of the best and sometimes hardest moves PFS has made.

Each partner has brought something unique and critical to the table. For example, when The Hershey Company approached PFS about becoming a partner, it expressed a keen interest in helping PFS expand into West Africa. With its support, PFS brought our program to Ghana and the Côte d’Ivoire. Along with that expansion, PFS began a collaboration with Root Capital, a social-impact investment company. Root Capital’s team provides asset financing and working capital loans, along with financial management training, to PFS partner businesses and performs an added layer of financial due diligence on potential clients that would otherwise be beyond our means. PFS in turn helps reduce the risk of their loans, by offering advice regarding who to provide loans to and how large a loan should be based on our specialized knowledge of the food processing industry.

PFS’s partnership with Root Capital also helped us employ our first PFS field staff in Africa—a food technologist and program manager in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Having our own technical staff on the ground has proven to be so beneficial to our clients and volunteers that PFS have since added five more staff members—one person each in Kenya, Zambia, Nigeria, and Uganda, and a second person in Ghana.

Partnerships also have helped PFS to leverage the investments of collaborators like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to multiply their impact in new ways: for example, using food fortification to address micronutrient deficiencies, the “hidden hunger” that has lifelong consequences for millions of people across the African continent.

Harnessing the Drive to Do Good. Volunteering brings out the best in a workforce, and we have learned that everyone has a desire to make a difference and contribute their knowledge in meaningful ways.

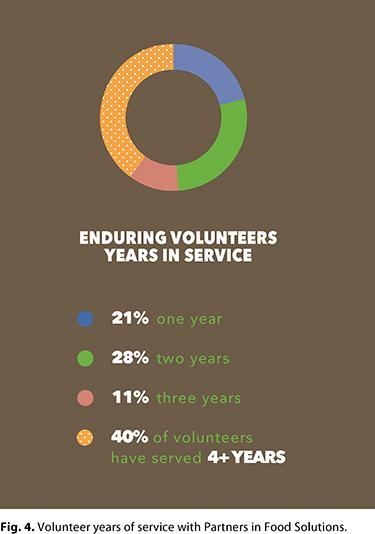

Nearly a decade ago the founder of Project Peanut Butter, an initiative to fight infant malnutrition, visited Minneapolis, MN, to talk to volunteers on a cold February day; we were worried no one would brave the –30°F temperatures on a Saturday morning to meet with him. Instead, 45 volunteers showed up, and as they spoke about their experience, we counted 700 years of experience being offered to help this worthy organization. The volunteers ranged in tenure at General Mills from 40 days to 40 years, and they came from different backgrounds, but they were all motivated by the same drive to help (Fig. 4).

Harnessing the philanthropic, collaborative spirit is a powerful underpinning of what we do at PFS.

Doing Good Makes Us Better. Learning and growth are bidirectional between PFS clients and volunteers. Professional development is fostered, which in turn strengthens the company through employee satisfaction, reverse innovation, and development of employee cross-cultural and managerial competencies. For example, Morgan Patrick, General Mills senior R&D scientist, used her work with PFS to gain invaluable leadership experience, acting as portfolio manager for the initiative’s work in Ethiopia with 20 clients and 75 volunteers—managerial skills she likely would not have acquired as quickly in her day job. Her global exposure, and the cross-cultural competencies, flexible mind-set, and creative problem-solving skills it fostered, eventually enabled Patrick to land a special short-term assignment working in a General Mills yogurt processing facility in France.

Tenacity and Creativity Are Infectious. PFS clients are resilient and succeed against the odds. We see daily the challenges they overcome and the innovations they continually manifest to make their businesses thrive, and it leaves a lasting impact on our volunteers.

Patrick’s work with enterprising, resource-strapped clients helped infuse her own work with a renewed sense of entrepreneurialism that can be challenging to evoke in a large, established company. Observing entrepreneurial behaviors and the drive to “get it done” with limited resources helps employees to reflect in their own work on creative ways they could attack a problem if they did not have a given resource at their disposal and learn how to generate that creative, hungry drive in their own projects. Patrick gives the example of an Ethiopian bakery that was having trouble procuring invert syrup needed for their cookie manufacturing business: “Rather than give up, they decided to just start making the syrup themselves, eventually turning it into an opportunity to sell it to other bakeries. Sometimes I try to remember this in brainstorming meetings around ingredient shortages or supply chain issues—how might we think about this differently? How would we make it if this didn’t exist?”

Change Is the Only Constant. When PFS was created 10 years ago, it looked very different. As an organization that was born out of the R&D shop at General Mills, one of our guiding principles is innovation, and we have continued to seek new ways to work with our partners and clients.

Going forward, we are looking for ways to apply the lessons of the past and fine-tune our strategy to produce an even greater impact. Because PFS have become more client-centric over time, we see their needs more clearly and are thinking about adjacent fields—other areas where the PFS model and access to expertise or valued resources can be established in the future. These may include certification in food safety, capital to unlock and accelerate investment, apprenticeships, aggregated purchasing, leadership training, and lab development.

PFS also is laser-focused on fast-growing food businesses with the most potential to reach smallholder farmers in need of good market opportunities, as well as consumers in need of nutritious, affordable foods. By the end of 2021, PFS aims to serve 300 food companies, with a focus on those 150 with the highest potential. Our target portfolio will collectively employ 17,000 people, have 1.2 million local farmers in their supply chains, and help improve the safety, nutrition, and access of at least 800 million meal equivalents annually in sub-Saharan Africa.

Although we did not know exactly where this initiative would take us, it was always predicated on the multiplicative power of knowledge and partnerships. These principles are being borne out in new ways. For example, the PFS model is being replicated in other sectors, such as a partnership with Business for Health Solutions, which is now underway, to apply the model to tackle some of the tremendous challenges the African continent faces in health care.

Although Kofi Annan’s passing unfortunately coincided with the 10th anniversary of PFS, we would like to think that he would be proud of us for answering the call he issued. As Annan saw clearly before we did, the global food industry has a key role to play in meeting many of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals: responsible consumption and production; zero hunger and no poverty; and decent work and economic growth, among others. We challenge ourselves and our industry to keep finding ways to harness and share its knowledge and innovations for the greater good. We can say from experience that it will only make our companies, our employees, our industry, and our world stronger.

John Mendesh spent 33 years with General Mills, serving as vice president for research and development. Today, he regularly volunteers 30–40 hours a week as a senior advisor for Partners in Food Solutions, an organization that he cofounded. A technical person by background, John is a chemical engineer who picked up an MBA along the way. During his three decades with General Mills, he worked on virtually every angle of food production. He developed new products for global cereals, directed international operations and supply chain for Yoplait, worked in engineering and manufacturing positions, and managed the corporate relationship with Cargill.

Peter Erickson is the former executive vice president for innovation, technology and quality at General Mills Inc., where he served in a variety of technical leadership positions since joining the company in 1988. Peter was responsible for leading a globally diverse team focused on the invention and commercialization of advantaged food products and technologies aimed at nourishing the lives of consumers, while cultivating trustworthy brands through rigorous attention to product quality, food safety, and technical excellence. He currently serves on the board of directors for Wenger Corporation, NobleGen Inc., and InnoCentive Inc., in addition to being a cofounder and past board chair for Partners in Food Solutions. Peter received both B.S. and M.S. degrees in food science at the University of Massachusetts, where he continues to stay involved as a member of their Food Science Advisory Board.