The Idea That Transformed the Carolinas

3 men tamed the Catawba River and brought electricity to Carolinas textile mills

Originally posted on Duke Energy | Illumination

The Carolinas we know today are shaped from Dr. Gill Wylie’s simple idea more than 100 years ago. He wanted to turn water into electricity.

And with engineer William States Lee Sr. and millionaire industrialist James B. Duke, they started building a series of dams along the Catawba River to provide hydroelectric power for textile mills. This investment drove growth and helped the Carolinas transform from an agricultural economy to emerge as an economic force with manufacturing, retail and financial services.

“Wylie grew up in South Carolina,” said historian Tom Hanchett. “He had one foot in the Carolina Piedmont and the other in New York where he’d received medical training and practiced after the Civil War. He was well read, educated and alive to possibilities. Electricity was the internet of its era, and textile mills were hungry for power.”

Large-scale electrification at Niagara Falls, N.Y., inspired Wylie to tap the power of the Catawba River near his boyhood home of Chester, S.C.

In 1895, he financed dam construction near Anderson, S.C., to supply the innovative hydro technology to textile mills. Five years later, he and his brother built a dam near Rock Hill, S.C., the beginning of what would eventually become 13 hydroelectric stations and 11 reservoirs spread across more than 200 miles of the Catawba-Wateree River.

But hydroelectric plants were expensive, and it wasn’t long before Wylie teamed with Duke, whose automation of cigarette manufacturing revolutionized the tobacco industry and made him one of the wealthiest men in the world.

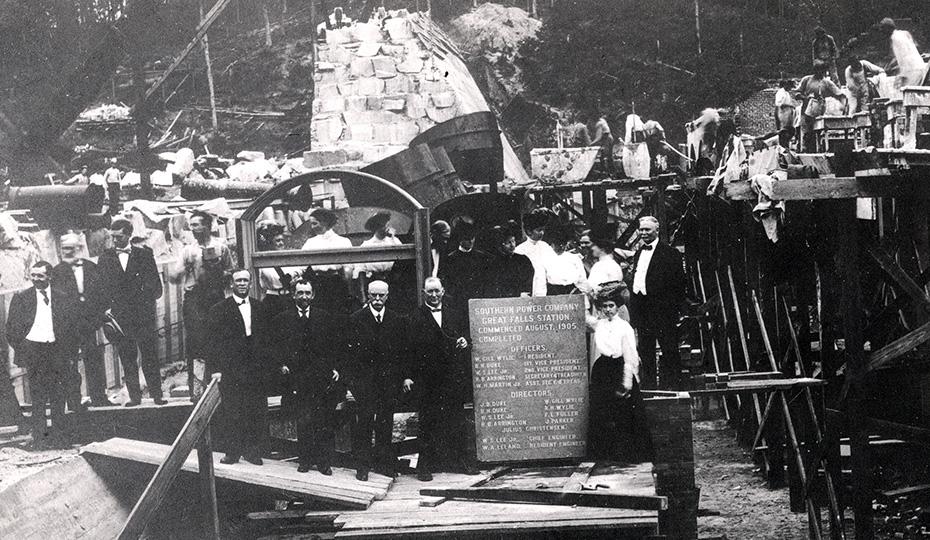

Duke bankrolled this venture, and with the engineering prowess of Lee, founded the Southern Power Company in 1905, a precursor to today’s Duke Energy.

Lee mastered the puzzle of long-distance power transmission. The “system of systems” connected power stations along South Carolina’s Catawba River and channeled energy to the state’s northern neighbor.

By 1910, Charlotte boosters claimed the region had more electrification than any other area in the nation, except for Niagara Falls. By 1920, more than 300 textile mills and other industries looked to Southern Power for electricity. The mills drew workers from mountain communities into growing mill towns and villages marking the beginning of a population shift.

The social and cultural transformation of the region shows how one cultural change set the stage for another, Hanchett said. The explosion of country and Bluegrass music is one example.

“These people had money in their pockets on payday Saturdays,” Hanchett said. “Groups of people could be an audience for music concerts – string bands and gospel music was the music from home. By the 1930s, Charlotte was becoming a major country and gospel hub.”

NASCAR’s roots and emergence in the 1940s extend back to the textile mills as well, Hanchett said.

“They ran races on Sunday after church. Most of the folks who came worked in the textile mills. Many of the people who worked on the cars were the loom pickers and machinery mechanics who worked on the mill equipment during the week and extended their skills to their stock cars on the weekend.”

By 1940, Charlotte’s population was more than 100,000 – five times what it was in 1900 – and it became a financial center.

Development along the Catawba reshaped the physical topography, giving rise to recreational opportunities on and around the lakes where hydro plants were located. Lake James, Rhodhiss Lake, Lake Hickory, Lake Norman, Lake Wateree and Lake Wylie give access to boating, fishing, swimming and water sports. Thousands of acres of new waterfront property spawned parks, golf courses, hiking trails and residential neighborhoods.

Even Charlotte’s Fountain View Road owes its name to the power of the Catawba River.

Duke was so enamored with harnessing the power of the river that he installed an elaborate “Wonder Fountain” in the gardens at his mansion in Charlotte and residents routinely witnessed the spectacle of water soaring 150 feet in the air.

While Duke and his partners are long gone, they left a lasting mark on the Carolinas.