How Genomics Will Support Gorilla Conservation

An Illumina iConserve project is mapping genetic diversity to identify where confiscated gorillas come from and boost survival rates

Originally published on Illumina News Center

Dr. Magdalena Bermejo is calling from a 50-square-meter house deep in a rainforest in the Republic of Congo. Her home and research station on the southwestern border of Odzala-Kokoua National Park, part of the Sabine Plattner African Charities (SPAC) World-Class Field Station Network (WCFS-Network), is one of the few places where large-scale studies of high-density western lowland gorilla populations are still possible.

This station is the permanent residence and lab of Magdalena, the head and principal investigator of the SPAC WCFS-Network, her husband German Illera, and seven other scientists. More than 30 students, professors, and scientists from Université Marien Ngouabi in Brazzaville and international universities regularly visit the station to participate in ongoing research projects supporting the survival of this endangered species.

“It is very important for science and for conservation to join primatologists in the field with geneticists in the lab,” says Magdalena. She believes in a multi-disciplinary approach when it comes to protecting species, bringing together scientists, academics, environmentalists, local residents, even politicians—all the people in her extensive network. “It’s better to collaborate between institutions, rather than compete. Instead of being protective of data, we must cooperate for the larger purpose of conservation.”

Classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), approximately 360,000 western lowland gorillas remain in the wild. However, poaching, habitat destruction, and disease are threatening their survival. Illegal trafficking continues despite international protection laws.

In West and Central Africa, organized criminal networks capture or kill the apes and export them illegally for consumption, private zoos, and trophies. According to UNESCO and UNEP’s report, Stolen Apes: The Illicit Trade in Chimpanzees, Gorillas, Bonobos and Orangutans, at least 98 gorillas were taken from the wild in a six-year time period. Between 2005 and 2011, more than 1,808 chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans were documented to have been captured from the wild for illegal trade. However, UNESCO and UNEP believe the number of animals that disappear is actually far greater than what is being recorded. Because so many die or are killed during the capture of just one individual, an extrapolation estimates that as many as 22,218 great apes were lost between 2005 and 2011. This, in turn, means disastrous consequences to the regions’ biodiversity.

For gorillas that are rescued from poachers and placed randomly in sanctuaries, the results can also be devastating. Gorillas have highly structured social behaviors and often die when forced to live with new groups. Infant gorillas, especially, are susceptible to stress and disease. Understanding a gorilla’s population of origin to potentially return them to the wild is critical to their survival.

Using cameras attached to trees, Magdalena and the primatologists are able to watch each group’s highly complex social behavior. The cameras are able to capture incredible detail, including such nuanced behavior as one gorilla communicating to another using only eye contact.

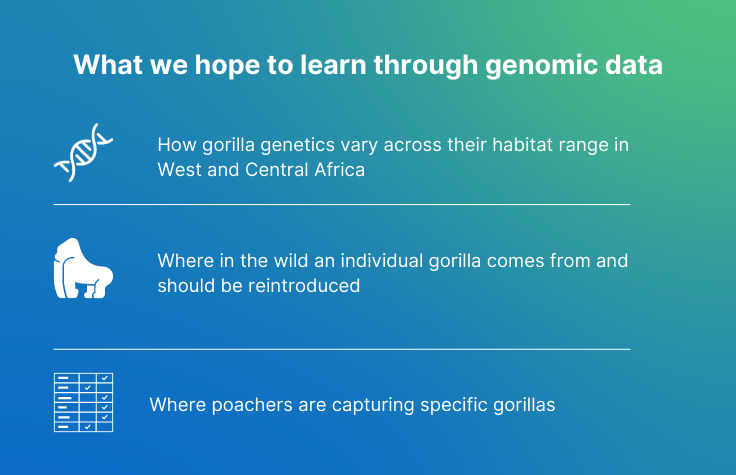

Identifying a gorilla’s population of origin

Today, Magdalena is partnering with Tomas Marques-Bonet, the head of the Comparative Genomics group at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, and the Illumina iConserve program to map the genetic variability of gorilla populations across their habitat range. Currently, there is no reliable molecular test to genotype confiscated gorillas, and there is no method to identify a gorilla’s population of origin. The mission is to create the first genomic atlas of gorillas in all countries and national parks so that future gorillas taken from the wild can be sequenced and matched to their population of origin. This tool will facilitate their relocation to a sanctuary close to their provenance, increasing the chances of successful reintroduction into their native groups.

“Thousands of animals are being moved every year, and the problem is that it’s very difficult to repatriate them,” says Tomas, who is the principal investigator on the project. “There is no atlas of where the gorillas are from because there are no forensic tools to geo-localize the animals. But a statistical genomic dispersion map of gorillas will allow us to see how the genome varies from east to west and from north to south.”

Sequencing gorilla DNA

To begin establishing a repository of gorillas’ genomic variation, a global network of primatologists is contributing samples in the form of gorilla feces. Some contributors have large collections of feces that they study for various purposes, while others will go to the field this year to get fresh samples for sequencing.

The first challenge is the logistics of getting thousands of samples from many different locations, and the second challenge is the sequencing technique. Whereas in clinical genomics, the samples usually come from human blood or tissue and the DNA is 100 percent human, in this project, the samples have gone through the animal’s digestive track, pulling only a small quantity of cells. “When we do extractions of DNA from the feces, usually less than one percent is gorilla DNA and 99 percent is bacterial DNA,” explains Tomas. In order to get good results, he must enrich the gorilla DNA in a molecular lab.

Dr. Magdalena Bermejo has been called at various times the Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey of western lowland gorillas. Among conservationists and academics, she is known as the world’s leading authority on these animals. Magdalena’s work at SPAC WCFS-Network is funded by the Hasso Plattner Foundation.

Magdalena and Tomas also have a goal to train local scientists, professors, and students from the nearby Université Marien Ngouabi to use next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology and methods to sequence future confiscated gorillas and enable authorities to act quickly. In addition to increasing the apes’ survival rate by returning them to their native groups, a genomic map would help authorities understand where animals are being poached, which in turn would aid local conservation and management agencies in their preservation efforts.

“A project like this is an unprecedented opportunity to show to the great ape community that genomics is a valid tool for conservation,” says Tomas. “This is yet another angle in which to approach a multifaceted problem, which is how to preserve a species.”

Magdalena’s team monitors and studies about 800 western lowland gorillas using over 60 high-resolution camera “traps.” Each gorilla group of five to 30 individuals will spend about two to three hours in front of the camera—the juveniles and infants touching, smelling, and playing in front of it, and the adults mining for tree roots, which they eat.

Using genomics to impact conservation

Hundreds of samples from Tomas’ collaborators at Uppsala University in Sweden, New York University, Czech Academy of Sciences, and SPAC are currently being sequenced at the Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico (CNAG) in Barcelona. “Illumina iConserve is a very forward-looking initiative,” says Ivo Gut, Director of CNAG. In the initial phase of the project, he is providing expertise in sequencing difficult samples and in developing protocols. The second phase will be facilitating the continuation of the project locally in the Congo. “We have the capabilities to do foundational work and with this, put tools into the hands of local people to use downstream technologies to protect and defend their local heritage.”

The Congolese are supportive of the research and new methods, and still Magdalena continues to educate—even those in the scientific community.

“When people in our network say, ‘Why genomics? It’s not our expertise.’ I tell them, ‘Well, at the beginning of my career I wasn’t studying cognitive neuroscience in gorillas,’” says Magdalena. “But what I know now is that if we don’t try to answer more complex scientific questions and be open to working with an international community of experts, then we won’t ever be able to make an impact in preserving this magnificent species.”