How Dairy Farmers Are Turning Manure

These New Englanders have found a way to help the planet and convert more than 9,000 tons of cow waste annually into electricity

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine

By Rachael Moeller Gorman

Photographs by David Degner

The Connecticut River cuts between the Green Mountains of Vermont and the White Mountains of New Hampshire and rushes into the heart of Massachusetts, where Denise Barstow Manz stands in the wind, surveying the land her family has farmed for 217 years.

“We have some of the best soil in the entire world,” says Barstow Manz. “It’s called Hadley silt loam.” She explains how the rich Connecticut River flood plain that’s wedged between the river and the Mount Holyoke mountain range behind her nourished tobacco, asparagus, broom corn and squash for her 1800s ancestors, and how it now grows hay and corn for the current farm’s 600 dairy cows.

Her dad, David Barstow, co-owns the farm with his brother, Steve Barstow, and his niece and nephew, Shannon and Steve II. David is “the director of special projects,” his daughter teases. “Anytime we are doing anything that is unusual, which is almost always, Dad is in charge.”

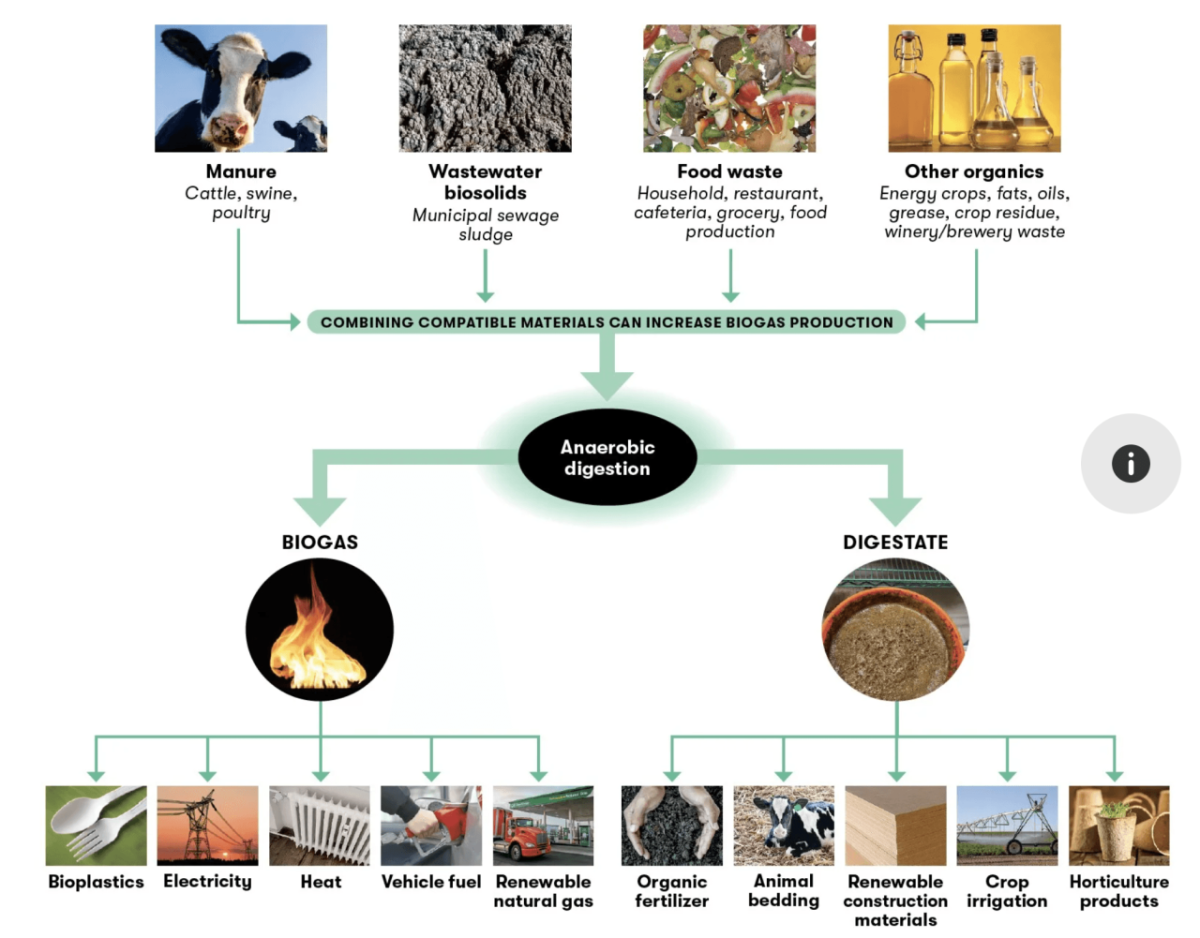

In the early 2000s, when the price of milk plummeted and dairy farms everywhere were trying to find a way to diversify, the Barstows began thinking about how to stay alive. They decided to take full advantage of an underutilized commodity the cows produced in abundance, and build something called an anaerobic digester—basically, a manure-fueled power plant.

It was a business decision that happened to have profound environmental consequences. Cows produce milk, but microorganisms in one of their four stomach compartments also produce methane. They belch methane out of their mouths, and when mountains of manure pile up in oxygen-free lagoons or pits, the micro-organisms keep producing methane there, too.