Good Towns: Nashville

From music to down-home food to the leaders who took on Jim Crow, we look at this city’s contributions to Black history.

Around the corner from Tootsie’s Orchard Lounge, across the street from the Ryman Auditorium, Henry Hicks sits under a sign that proclaims, “One Nation Under a Groove.”

Hicks, more formally known as H. Beecher Hicks III, is the CEO of the sparkling new National Museum of African American Music. And, for a few minutes, he’s taking the time to observe as visitors stroll in.

“I come into the gallery a couple of times a week, but I’d say this is my favorite spot,” Hicks said. “I love to sit here, see the people go in curious and come out enthusiastic about what they witnessed.”

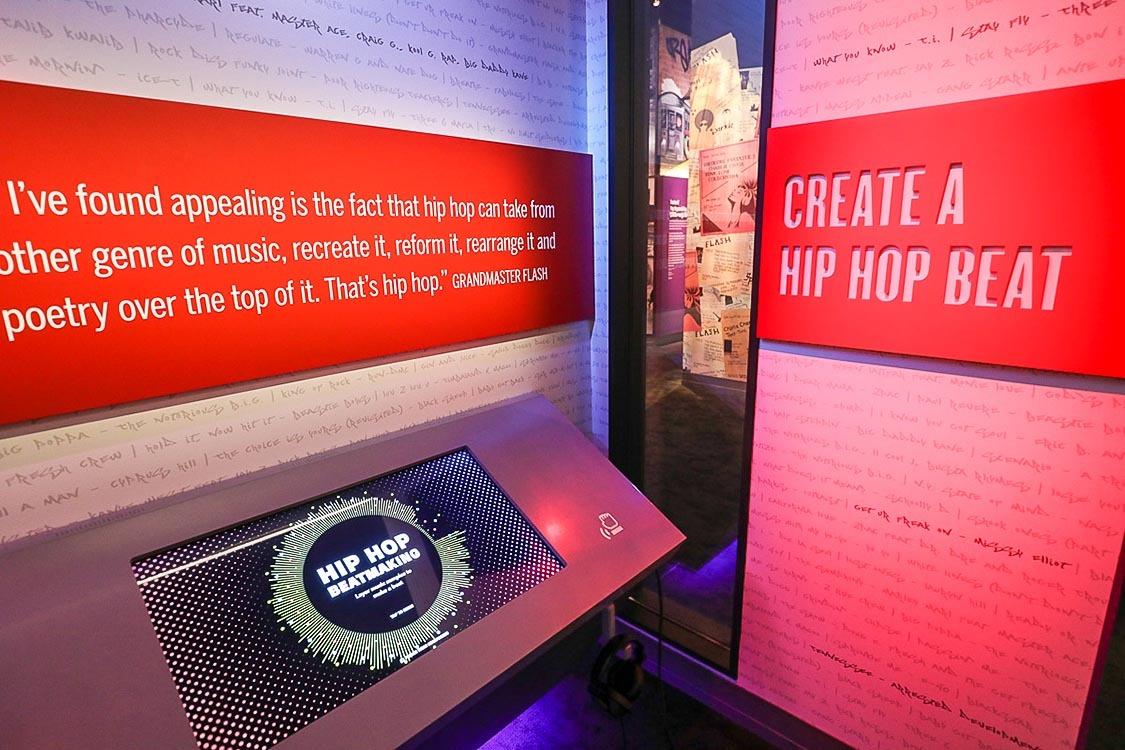

Opened in 2020, the museum adds significantly to Nashville’s Music City brand. Because long before country music established a stronghold over radio, African American music ignited the genres we associate with contemporary standards today – from gospel and spirituals, to jazz, the blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

And, yes, country music.

When WSM’s Grand Ole Opry first hit the air, becoming an institution that remains Nashville’s music lifeblood a century later, DeFord Bailey was there, on stage. The grandson of slaves, Bailey learned to play the harmonica as a child while bedridden for a year after contracting polio.

When his father landed a job in Nashville, Bailey began performing locally, gaining a reputation that carried him all the way to the Ryman stage before a national radio audience.

For Hicks, bringing the museum to fruition and raising funds to ensure its longevity is a labor of love.

“I think the interactivity surprises visitors the most,” Hicks said. “We wanted to appeal to multiple generations and how it speaks to people individually. You can find your music here and build your own playlist. It’s not just about artifacts. This is something you can take with you.”

You can spend an hour or get lost for days touring the museum. The Roots Theater offers an immersive visual and audio experience that traces music to its African beginnings, brought to America by slaves, before evolving through history – from Reconstruction to world wars to the Jim Crow South.

Other galleries are just as mesmerizing. Wade in the Water brings the religious experience from the 17th century onward. A Love Supreme focuses on the Harlem Renaissance and emergence of jazz. One Nation Under a Groove documents the evolution of rhythm and blues from post-World War II to a unifying force during the Civil Rights Movement. If you love Motown, you’ve found heaven.

Latrisha Jemison joins us for the tour. She’s the Regional Community Development Manager for Regions Bank, based in Nashville.

“I’m a member (of the museum) because I’m proud of the fact this incredible museum is in Nashville,” Jemison said. “I love music and I’m honored that I come from a culture that produced this magic. Just growing up, Prince and Michael Jackson were the tapestry of my life.”

Regions has been a sponsor the museum since it opened doors 18 months ago.

“In all sincerity, Regions stepped up early,” Hicks said. “That enabled the community to see there was support, and it allowed corporate leaders to see how important this was.”

Jemison said the decision for the bank to be a part of the museum was an easy choice.

“Regions is a mainstay in Nashville, and with something this important we had to be a part of it,” she said.

Where Ideas Became a Movement

A group of college students first put the Music City on the map – at least in terms of harmony.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers debuted in 1871, five years after the founding of the university at the conclusion of the Civil War. Bringing “slave songs” to the mainstream, the Fisk Jubilee Singers gradually spread their wings. By the end of the 19th century, the collegians were headed to Europe, performing for heads of state. More recently, they headed to Ghana at the invitation of the U.S. Embassy to perform as part of the nation’s Golden Jubilee in 2007.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are a big part of the National Museum of African American Music, and they are honored in numerous ways on Fisk University’s campus in North Nashville. But Fisk’s involvement in American history goes much deeper.

W.E.B. Du Bois graduated from Fisk in 1888, founded the NAACP and became one of the most strident voices of the early Civil Rights Movement. Artisans, including poet Nikki Giovanni and dancer Judith Jameson, are more recent graduates.

A freshman at Fisk in 1959, Diane Nash went from coed to movement leader two years later during the Freedom Rides. At the same time, a young man from South Alabama who came to Nashville to become a pastor instead became a fixture of the movement – from Nashville sit-ins to the halls of Congress. His name: John Lewis.

You can argue that Selma and Birmingham were the frontlines of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. But it was Nashville that first inspired change, taking Jim Crow laws and racism head on. The city has always had strong academic credentials, especially for young Black students. Local Historically Black Colleges and Universities include Fisk and Tennessee State University, which lure undergrads from across the nation, and Meharry Medical College, the original trailblazer for Black physicians and biomedical scientists. And if Fisk, TSU and Meharry helped shape generations of minds, American Baptist College, a Baptist seminary, has helped save souls since 1924.

In 1960, this convergence of academia and idealists seeking equality for all Americans placed the city on a stage that exceeded the Ryman Auditorium’s reach. Nashville sit-ins launched the peaceful protest, the hallmark of the Civil Rights Movement to come, and protests against segregated lunch counters throughout the South.

Coordinated by the Nashville Student Movement and the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, the sit-ins featured college students who defied archaic laws to eat lunch elbow to elbow with whites. They did so quietly, yet defiantly, across downtown Nashville, subjected to verbal and occasional physical abuse as the eyes of the world watched.

For four months, the protests continued. So, too, the pushback, yet the numbers of supporters swelled. A march of 3,000 black Nashvillians to City Hall in April of 1960 finally brought constructive change, with Mayor Ben West agreeing to integrate lunch counters in downtown Nashville.

With leaders like John Lewis, the momentary victory would lead to the Freedom Rides in 1961, and then to Birmingham and Selma in search of voting rights, igniting change that led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The United States Civil Rights Trail commemorates the moments and the movements with a walking tour that encompasses the National Museum of African American Music and the Woolworth department store downtown (a key site of the sit-ins), to the Fisk campus and Clark Memorial Methodist Church in North Nashville to American Baptist College just across the Cumberland River.

Birthplace of the Meat-and-Three

Lethia Mann was 7 when she accompanied her father to a local bank, in search of a loan. Most children go inside a bank and tend to be bored, but Mann saw the moment as magic.

“I thought this was what I wanted to do,” she said. “And I did.”

While she eventually became a banker – she serves Regions in Nashville as a Community Development Manager – she first had to help her parents back at the restaurant. She started working at Swett’s Restaurant while in junior high, then continued as a college student at Vanderbilt.

Now she comes back regularly, as do most Nashvillians. Because Swett’s Restaurant is an institution.

On the wall are celebrities who once ate there – musicians from Lionel Richie to Little Richard, Toni Braxton to Randy Travis. Former Tennessee Titans quarterback Steve McNair was a regular and John Madden often stopped by when in town to broadcast a game. Actors Danny Glover and Fred Thompson have a spot on the unofficial wall of fame, too. Politicians from across both sides of the aisle make an appearance.

There’s also a copy on the wall of the 1961 Green Book, the guide for Black travelers during the Jim Crow era, touting Swett’s as the place to go in Nashville. Other businesses are listed, as well, but only Swett’s and a local beverage store remain in operation.

A mural on a far wall that you pass after you pay for your meal tells the family’s entrepreneurial history, how Walter and Susie Swett once owned a full-service gas station and grocery market.

David Swett, one of 10 children Walter and Susie reared, oversees everything with a gentle smile and a twinkle in his eye.

“On Sept. 11, 1954, my parents opened Swett’s Beer Tavern, where you could get beer and sandwiches,” he said as we shared a meal. “My mother, Susie, decided to fix lunches: fried chicken, meatloaf, turnip greens, candied yams, mac and cheese …”

And thus, the staple “meat-and-three” was born.

Like Lethia, his niece, David worked odds jobs for his parents in high school and while a student at TSU. “I didn’t volunteer,” he laughed. “I was drafted as a pot and dish washer.”

David took over for his parents in 1969. A decade later, Lethia’s father joined the management team, remaining until his death in 1995.

The current restaurant, which David began planning for in 1984, is now an institution. So is Swett’s Plaza, a shopping center across the street, just blocks from the Fisk, Meharry and TSU campuses. On Saturday football homecomings in the fall, TSU fans line up for blocks to get in. During the week, the traffic is steady and diverse. But things are changing fast in the neighborhood because of gentrification.

A new home directly across the street is on the market for more than $1 million. In blocks all around, old shotgun houses are disappearing in favor of “skinny houses,” three-story luxury homes and apartments on small plots.

Swett’s popularity never seems to wane. Even after 50-plus years in charge, David Swett doesn’t like to take time off.

“This business is only for specific types of people,” he said. “We work seven days a week and we’re open from Jan. 2 to Dec. 23, nonstop. There’s no time to relax because a crisis is just around the corner. Something breaks down or somebody doesn’t show up for work. You never know.”

Customers stop to say hello or give a shoutout to their meal. Swett greets everyone like they’re old friends.

He’s been offered chances to franchise, to expand the brand. And for a half-century, he’s resisted the overtures.

“It’s not like cooking a burger on a grill,” he said. “This is home cooking. I’d rather run one restaurant successfully instead of 10 with mixed results.”

And he has just one rule in an age where most service industries have trouble keeping employees.

“You’ve got to be disciplined, and you’ve got to be here when you’re supposed to be here,” he said. “I’ll be involved here until the day I die. I’m never going to stop working.”