Creating Strong Bridges to Biotech: Professional Development in Action

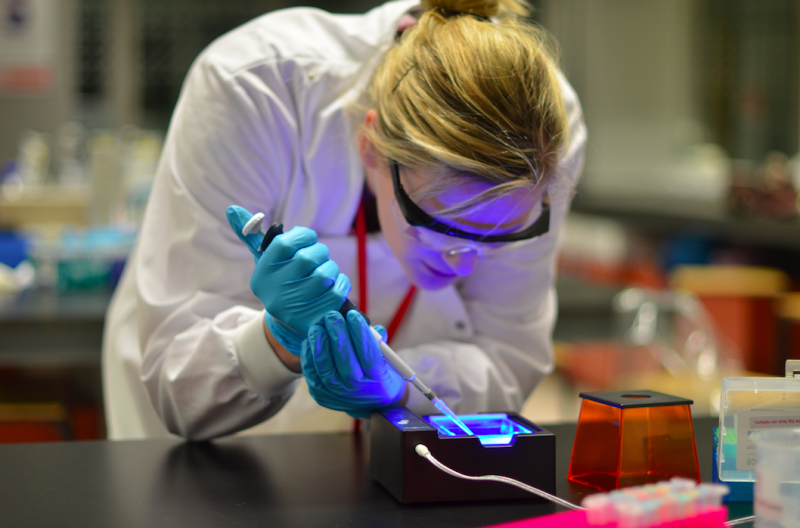

School is out for summer – or almost – for most high school students globally. But for some teachers, the learning is going to continue. Around the world, Amgen Biotech Experience (ABE) sites are gearing up for their professional development institutes, or PDIs. These multi-day workshops train high school teachers in the ABE curriculum, directly giving them experience with the hands-on biotech labs they’ll run in their classrooms when school resumes in the fall.

“Teachers feel intellectually fed when they go to the PDIs because they get a chance to be learners again,” says Jessica Juliuson, who leads professional development and networking for the ABE Program Office. Over the course of the school year, teachers can often feel isolated working alone in their classrooms, and the PDIs offer the opportunity to connect with their peers while throwing themselves into an exciting content area. The science they are learning is often more cutting-edge than what they have previously learned, Juliuson explains, and the institutes are “a way for them to ask questions in a safe environment.”

ABE survey findings echo these observations, with more than 90% of respondents giving PDIs a high approval rating and the majority of participants reporting an enhancement in their interest, knowledge, and skills. However, surveys have also shown some inconsistencies across the program sites in terms of what each PDI covers; part of this is due to regional needs and customizations, but some differences may result from gaps in onboarding, differences in prior teacher training, or differences in intended outcomes. In response to this feedback from teachers, Juliuson and her team are working on a new framework to bolster professional development approaches network-wide.

While the primary goal of the PDIs remains the same – to enable teachers to facilitate hands-on biotech activities with students – a secondary goal that will be more prominent in the new framework is to strengthen general teaching strategies. This can include everything from how to work with students with a range of differing learning needs, to how to take a more reflective approach to the materials, giving students time to ask open-ended questions within the curriculum.

“The goal is to take previous PDI designs and start to flesh them out and annotate, to suggest new things teachers might try in the classroom,” Juliuson says. This summer, parts of this new framework will be piloted in PDIs in Boston and San Francisco. After these pilots, the ABE team will gather data and evaluate how to proceed with the ABE PDIs. “Our real lever here for good professional learning is the idea of building a community of practice, equipping teachers to draw on each other so that they don’t have to constantly reinvent the wheel,” she says.

While building this community of practice and developing a common scaffolding for the lab experience, the ABE Program Office knows that sites will still necessarily vary in how they approach the curriculum. This diversity reflects the international reach of the program. In Australia, for example, the geographic region covered by the program is vast, with significant differences between the urban areas and more rural ones with higher percentages of Aboriginal populations. That means their PDIs have to equip teachers who work in a wide variety of settings. The various sites globally may also approach the curriculum itself slightly differently, to make sure it connects to actual science trends in their countries.

A former English and social studies teacher, Juliuson sees that education in all disciplines has become less relevant and more disconnected for students over the years and sees programs like ABE as a way to bridge students and teachers to the real world. “This model is the way to go,” she says, “to create the building blocks to prepare students for the real world, while motivating and engaging them and showing them why the science matters.”