Cleaning the Built Environment After the Big Celebration

by Daniel Rosen

CBRE Blueprint | Play of the Land

The city of Philadelphia’s football team won the big game for the first time ever and its long-suffering fan base celebrated the victory in kind. In February, the city held a massive parade for its football team, a turnout that some estimated teetered over 700,000 people (a spokesman for the City of Philadelphia did not have an official tally). With this great turnout came its inevitable byproduct: trash. Lots of trash. Roughly 90 tons of trash, the most the city has ever generated for a single event and nearly double its previous record of 58 tons for a victory parade for its baseball team in 2008.

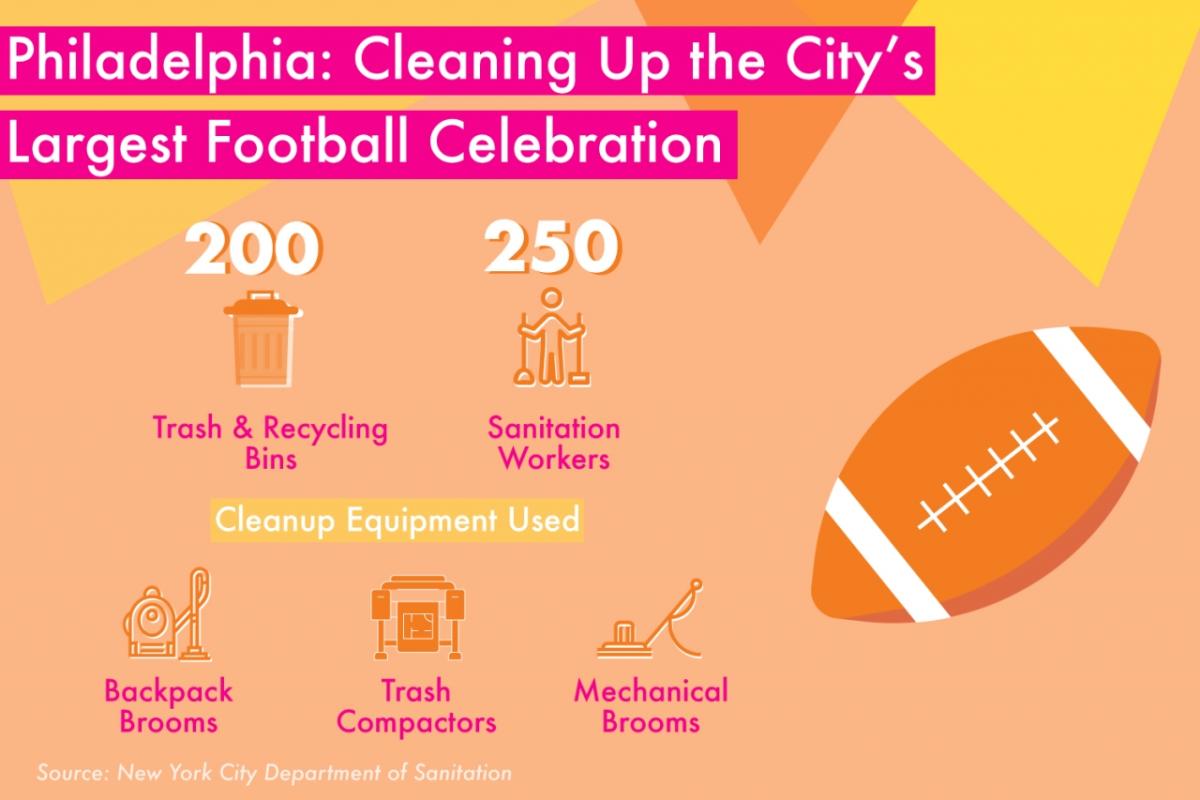

Philadelphia came prepared. The city’s Department of Streets mobilized a team of 300 workers, using 100 kinds of equipment, to follow the procession of the parade to clean up the immediate aftermath. Approximately 200 metal and plastic trash cans and recycling bins were chained to poles along the parade route. It proved to be a successful plan of attack.

“We were able to get things cleaned relatively quickly without interruption and with the goal of making it look like nothing even happened here in the city of Philadelphia,” says Carlton Williams, commissioner for the Department of Streets, in an interview with Blueprint, Presented by CBRE.

Whether it be a sports parade, New Year’s Eve in Times Square, or Mardi Gras in New Orleans, these kinds of mass gatherings in popular public spaces require an efficient plan of attack to tackle the considerable amount of waste that these events can generate without sending this waste to landfill.

The success of these cleanups hinge on the new and innovative ways cities are approaching waste management, ultimately with an eye towards becoming nearly waste-free in the near future.

“Waste is an actual resource to be harvested and ultimately it’s important how we manage those resources because they have environmental and economic benefits,” Williams says.

NEW YEAR’S AND MARDI GRAS

The New Year’s Eve bash in New York City attracted nearly 1 million partygoers to cram into Times Square and brave the cold temperatures to welcome 2018. Once the iconic New Year’s Eve ball dropped, a team of 294 from the City Department of Sanitation was deployed to clean up the estimated 50 tons of confetti and debris using 58 backpack blowers, 30 mechanical brooms, 44 collection trucks, and 58 hand brooms, per the Department of Sanitation.

It takes upwards of 16 hours to clean up the New Year’s mess. In addition to its efficient approach to cleaning up after the party, New York City already embarked on its Zero Waste plan with an eye towards reducing waste output by 90 percent by 2030.

“The average New Yorker throws out nearly 15 pounds of waste a week, adding up to millions upon millions of tons a year,” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio told The Associated Press in 2015. “To be a truly sustainable city, we need to tackle this challenge head-on,” de Blasio added.

To achieve this goal, the city has set out new initiatives like enhancing its curbside recycling program by offering single-stream recycling, where residents can mix various recyclable materials instead of separating them; reduce the use of plastic bags, make recycling of textiles and disposing of electronic waste more widely available (clothing and textiles make up 5.7 percent of the city’s total waste); and reduce commercial waste disposal by 90 percent.

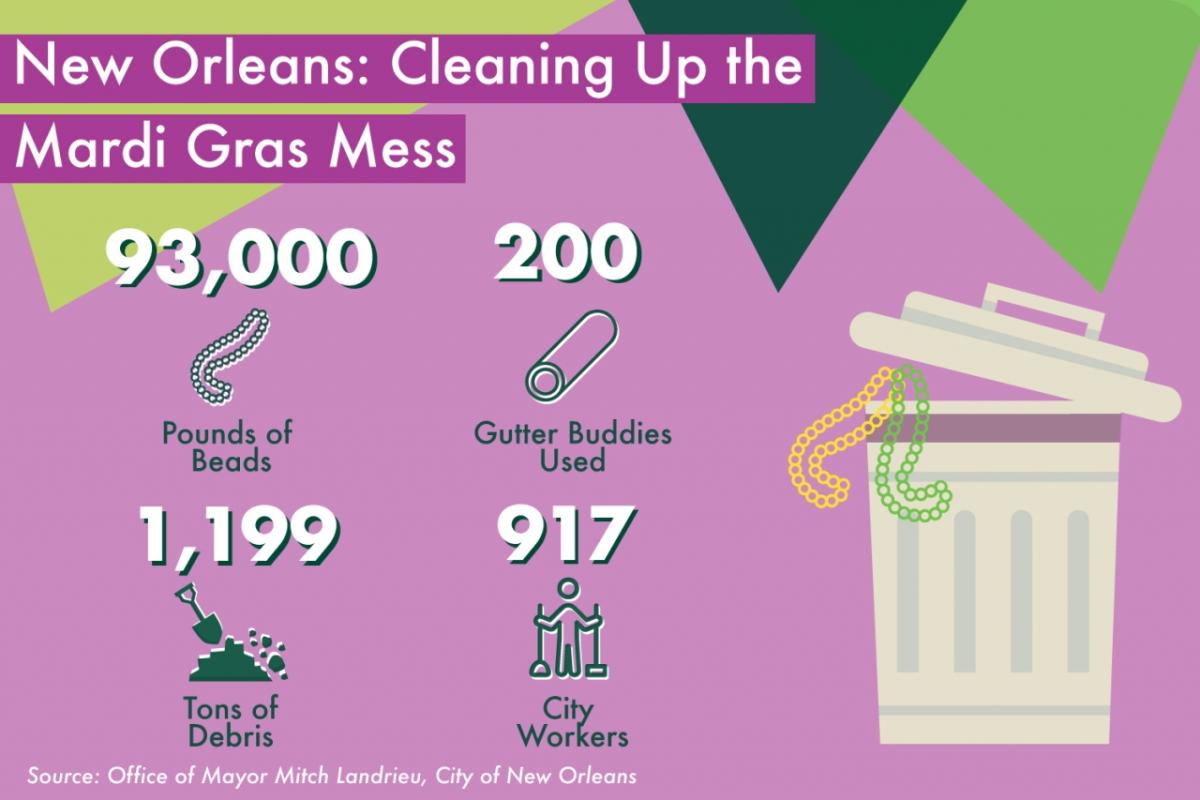

In New Orleans, which recently wrapped up its Mardi Gras celebrations, the city deployed 917 worker (a mix of city workers, temporary workers, and contractors) to clean up 1,199 tons of debris. The beaded necklace, a Mardi Gras staple, had proved to be a toxic headache for the city. Between September 2017 and January 2018, of the 7.2 million pounds of debris that was generated during that timeframe, 93,000 pounds of that were Mardi Gras beads alone that were retrieved from 15,000 catch basins throughout the city.

To prevent these beads from ending up in city catch basins, New Orleans installed 200 “gutter buddies” that work to prevent debris from entering catch basins.

CLEAN PHL

To help accomplish its goal of becoming waste-free by 2035, Philadelphia launched Clean PHL to introduce new measures and refine existing ones to eventually eliminate the use of landfill and conventional incinerators. This includes investing in single-stream recycling and stopping illegal dumping. Clean PHL is examining every avenue where waste is generated, “from the largest corporation to the smallest household,” Williams says.

“Managing waste should be more than just recycling. (The focus) should be on how products are created versus how we dispose of them. It’s looking at the products at the beginning of their lifecycle and ultimately looking at an intended use for it,” Williams says.

Sweden has proven that zero waste is a real possibility. Less than 1 percent of Swedish household waste was sent to landfill between 2011 and 2016. In 2016, nearly 2.3 million tons of household waste was turned into energy through burning.

Williams is optimistic that Philadelphia can reach its zero waste goal by 2035 and create a new sustainable waste management system.

He says: “I think people are now realizing that waste is more than just something to be discarded."