Banning Charcoal Isn’t the Way to Go. Kenya Should Make It Sustainable.

Why has the government clamped down on charcoal trading?

The government is concerned that charcoal production is leading to the destruction of Kenya’s environment.

Charcoal is made when wood is burned in a low oxygen environment and burns off compounds like water, a process that can take days. Some tree species, like Acacias, are preferred as their charcoal burns longer. But once these preferred tree species are all used up, producers will fell any tree. When trees are cut down, and the land is left bare, rain water runs off the surface eroding fertile topsoil. Groundwater supplies are also affected because tree or vegetation cover ensures water seeps into underground wells.

That said, there are some big misconceptions about the charcoal sector and its role in environmental damage. The production and use of charcoal is not a bad thing in itself. Trees are a form of renewable energy. Secondly, charcoal receives most of the blame for the loss of trees, but other factors – like the clearing of land for agriculture or pasture – are also to blame.

Kenya has imposed a charcoal ban before. The bans are largely based on the assumption that charcoal is acquired from government land. But most charcoal in Kenya is sourced from privately owned and managed land. This makes the bans ineffectual.

How is the ban being enforced and is it sustainable?

The measures include a ban on production and restrictions on transportation and trading. These are unlikely to resolve the problem and may create new ones. It’s important to get the approach to charcoal right because so many producers and users rely on it.

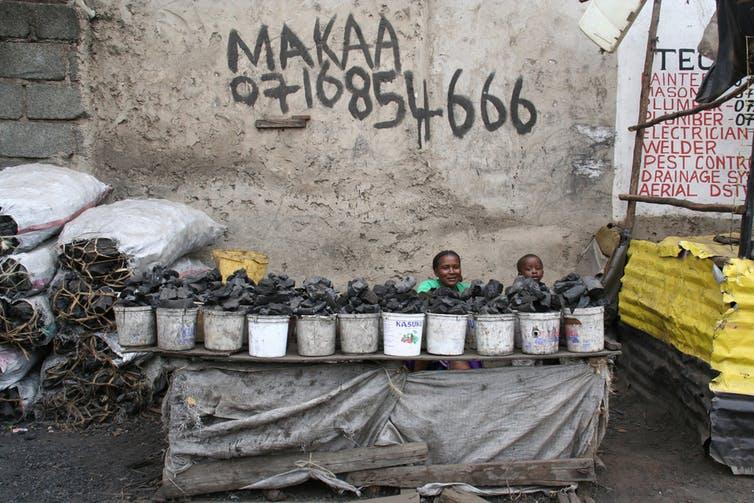

Wood energy has been used for millenia. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 62% of global charcoal production. In Kenya, the charcoal sector is worth about USD$427 million each year – almost the same size as the country’s tea sector. And about 80% of urban households depend on it for cooking.

Most people who produce charcoal live in drylands and do it as a source of income. Drylands make up over 80% of the land in Kenya. In some of these areas, about 50% of the households depend on charcoal as their main source of income.

The important issue is that, despite the high dependency on charcoal, existing regulations for a sustainable charcoal sector production are not being applied in a sustainable manner. The majority of producers don’t have tree replanting schemes. They also use wet wood in earth mould kilns to convert wood to charcoal. This produces a low conversion of wood to charcoal, meaning wood is wasted, land is degraded and air polluted.

Who is most affected by the crackdown?

The ban mostly affects the users – who are middle and low-income households, mostly in urban centres.

Charcoal prices have gone up by 27% in the past month. It now averages 107 shillings (about USD$1) for less than 2kg of charcoal. One person uses about 1.9kg of charcoal a day. When earning less than USD$2 a day, this means sacrifices have to be made.

If people can’t afford charcoal they turn to unsafe cooking methods, like burning plastic. This can have a huge negative impact on health as the most affected urban dwellings are usually small and poorly ventilated.

If the ban is successfully implemented will it have a significant impact on the environment?

No. Far too many people rely on the charcoal industry to rule it out, so it must be made sustainable. A number of reputable organisations in Kenya, such as the World Agroforestry Centre, Food and Agriculture Organisation and Kenya Forestry Research Institute, have demonstrated how charcoal can be produced efficiently and effectively.

The first stage of the supply chain is sustainable wood production. There are different methods of sustainable wood production including tree plantations and community managed woodlands. There is also tree inter-cropping where farmers grow trees alongside crops or in a separate woodlot. A rotation system can be used where trees are cut in a specific order or mature branches harvested, ensuring constant standing biomass. Farmers could also harvest some trees then let the area naturally regenerate, protecting young shoots from being eaten by livestock.

If dryland communities sustainably managed woodlands, charcoal that currently threatens these ecosystems would turn into a livelihood strategy. Unfortunately, these options have not been widely adopted – a factor that could be contributed by low government budgets in charcoal and firewood programmes.

The next stage is to use efficient kilns to convert wood to charcoal. In most places people use kilns that convert just 15% of the original wood weight into charcoal. Yet there’s a lot of research and development in kiln technologies – with some achieving over 30% conversion efficiency. One of the main reasons why these efficient kilns aren’t being used is a lack of awareness and cost. If charcoal production was effectively supported, it would inform producers on the benefits of better kilns and encourage them to invest.

And then there are markets. Central areas for collection and transport of larger quantities would reduce costs and emissions. This should be put into place by county governments.

Finally, it’s important to address the end use of charcoal. Households often use more charcoal than necessary, due to stoves which have low energy conversion efficiency – sometimes less than 15% . They need to use improved stoves, with over 35% energy conversion, to reduce household charcoal demand. Commercial enterprises that use charcoal should also follow suit.

The reasons these technologies haven’t been implemented is that Kenya, like other African countries, needs a perception shift. Government, researchers and the public need to understand that charcoal can be made sustainable. A pro-firewood and charcoal shift will see the development of technologies for sustainable wood-based energy in the country. Once we have that, the budgets will come through and it’ll be properly rolled out.

Mary Njenga, Research Scientist, Bioenergy, World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.