Art and Understanding: Regions Bank Celebrates Diversity Awareness Month

Regions Bank Diversity, Equity & Inclusion networks celebrate associates and communities.

By Evelyn Mitchell

“I think every human being is born an artist. They just need to find what that art is.”

Katrina Mitten

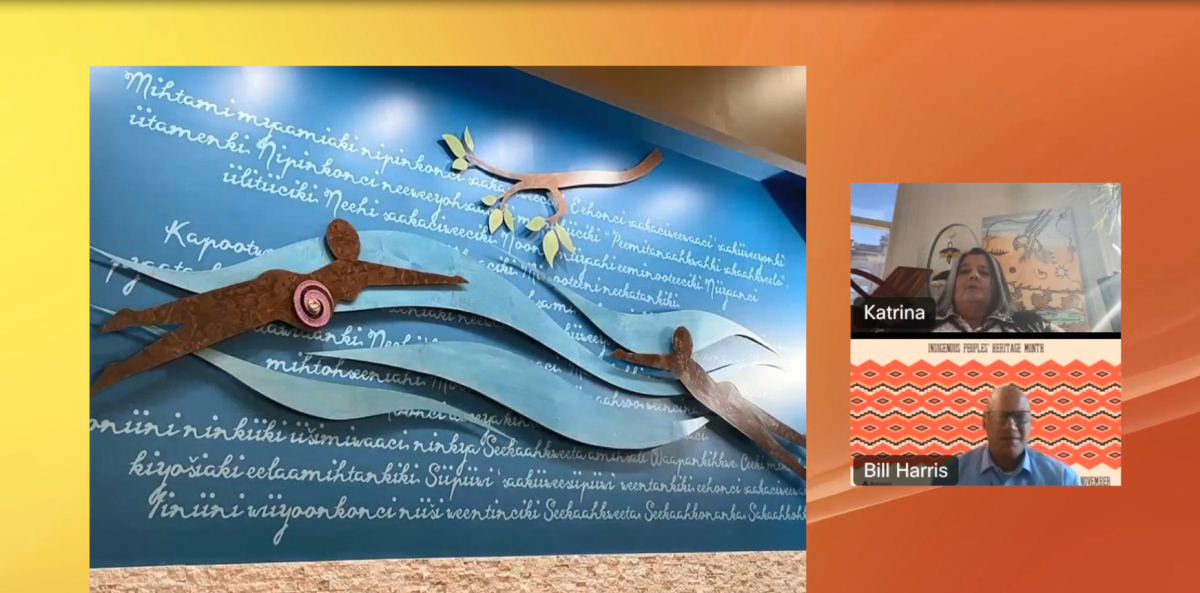

Regions Bank’s Indiana Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Network and Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis hosted award-winning Native American artist, Katrina Mitten, for a conversation on her art, history, and culture as a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

Regions’ Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Networks represent more than 14,500 associates across 25 markets and all business groups. They are associate-led networks established geographically, whose mission is to help build deeper connections, greater understanding and a stronger sense of belonging within Regions. One way Regions’ DEI Networks bring this mission to life is through interactive programming.

Bill Harris, Chair of Regions’ Indiana DEI Network, facilitated the event. What follows are highlights from their conversation, edited for brevity.

Bill Harris

One of the most important messages the Eiteljorg (museum) strives to convey is that Native Americans are still here. They did not vanish. Native Americans live, work, play, and create communities all across the country. You’re a lifelong resident of Indiana, and a citizen of the Miami tribe of Oklahoma. Can you tell us how that works?

Katrina Mitten

Well, when our people were removed from Indiana forcibly by the United States government and because of signing treaties, we were removed from Indiana to Oklahoma or Indian Territory, which originally Kansas was part of that, and then Oklahoma – our tribe was moved twice. But there were five families that were allowed to stay in Indiana because they had either businesses or farms already and it was negotiated during the treaty signings that those people were allowed or were able to stay here in Indiana. And my family, the Richardville ...they were allotted lands here and allowed to stay.

Bill Harris

Can you tell us when you started working with art and what that means you?

Katrina Mitten

Well, growing up here in Indiana, when children go to school, in the fourth grade they learn about Indiana history. And so, they were hearing about my family and some of it wasn’t being taught like it should. It wasn’t our version of the stories that came out of our history and what happened to our people. And I knew that as a young child.

When I was around 12 years old, I decided I wanted to learn something. I believe I was born an artist. I think every human being is born an artist. They just need to find what that art is. ...And in my 12-year-old brain I was thinking beadwork. It was the early ‘70s so I decided to use beads, because even in the small town of Huntington where I live, there was a store where a woman had beads for sale. The love beads that were all different colored beads. I would cut them apart and I sat and I taught myself how to do loom work. But then soon after, I decided I didn’t like using a loom as much. And so I moved on to looking at a couple of small pieces that my grandmother had where the beads were sewn directly onto fabric.

Bill Harris

So how do you feel like growing up in Indiana – how did that affect your art or kind of the pieces that you chose to do?

Katrina Mitten

Well, I think that growing up in Indiana, I was away from our people because those who were allowed to stay here or were able to stay here, we were also far apart from each other. And we had to assimilate into the dominant culture. We couldn’t speak our languages, we couldn’t do our art, our traditional arts, because that would identify us as being native people, and we weren’t treated very well. The assimilation kind of put a kink in what we could do that was traditional to our people. And so, I didn’t learn from my grandmother how to do beadwork. Like I would have, you know, pre-removal.

So, it was hard for me to. Especially at the age 12, the first piece I did was a very Pan Indian is what I call it. It’s that style from the ‘70s and the ‘60s of Indian trinkets and the designs. It was very simple. Black thunderbird, white background with red and yellow connected diamonds. And I sewed it on the back of a fringed leather jacket.

I got married, I had my children young. And so, while they were running around, you know, banging on pots and pans or watching Sesame Street, I could still sit and bead. And as I got older, we would get out to pow wows and things and we would head up north into Michigan to be around more native people and I would learn from what those people were doing also.

Bill Harris

What do you hope to achieve through your art? What’s the larger goal for you with your art?

Katrina Mitten

The larger goal is to get people to know and who our people are, the Miami. We had so much to do with the forming of this country. And we were a very large tribe at one time. But people don’t hear of us. ...It’s growing because we’ve worked so much on our language and other things.

Bill Harris

Can you talk about what you’re doing, transitioning that to the next generation?

Katrina Mitten

I say, what’s happening is that link was broken. Within our people and our culture, because of our people being removed and us assimilating that I talked about earlier, I had to teach myself. Now I’m bringing that link back together as a grandmother teaching her granddaughter to do a traditional art and that’s very important for all tribes to be able to do that.

The Miami people have been doing so much. We’re bringing back our language – but that was almost lost. We say it was sleeping. It was just waiting for the right time to come back. Bringing those things back to our children is really important.

Bill Harris

I know artists are always connected in some way to their work, but when they create something that particularly has special meaning to you, how is it hard to, you know, decide to sell it or part with it?

Katrina Mitten

You know, that’s a really great question and I get that sort of a question all the time because when you do things with your hands, it does become a part of you. Any art that you do would be hard to give away, you know, or sell. But I look at most of my pieces, they have stories that go with them, and my goal was always to educate other people about who we are as Miami people. By those pieces selling and going to a museum or someone buying it for their home, their collection, the stories go along with it. So, they’re learning, and (others) will learn from them, from that piece, also.