Americans Are Starting Microbusinesses To Overcome Economic Struggles

More government support and better networking could further their success

Originally published on Venture Forward by GoDaddy

The pandemic has been particularly punishing for the 42% of Americans who live at or near the poverty line, according to United for ALICE, an arm of United Way that studies this demographic group. So what are these people doing to make ends meet? Some of them are starting online microbusinesses. While there has been an overall boom in microbusiness starts since COVID-19 hit, people whose income lags behind the estimated cost of living in their area were more likely to have started their business since 2020, new Microbusinesses and Resource Constraints White Paper by Venture Forward has found.

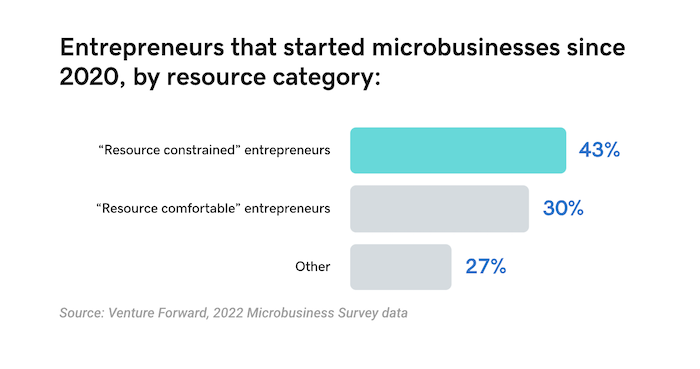

According to Venture Forward’s 2022 Microbusiness Survey, 43% of “resource-constrained” entrepreneurs said they started their microbusiness since 2020, compared to just 30% of wealthier “resource-comfortable” peers.

“Communities where the cost of living is higher than the average income in that community are adopting microbusinesses and turning to internet commerce at higher levels than in areas where people have enough to pay for life’s necessities,” says GoDaddy senior scientist Kellen Gracey, who led the research project.

Indeed, the percentage of owners who said they started their business out of necessity – to keep food on the table, rather than to attack an exciting new market or pursue a passion project – rose from 14% before the pandemic to 25% in 2020 before settling back to 21% for the 2020-2022 period.

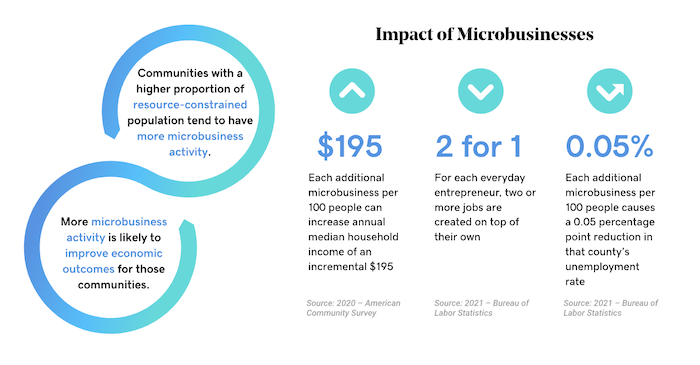

This spurt of business creation helps explain another new finding from the research: areas with a higher percentage of people who are struggling economically tend to have more microbusiness activity than wealthier ones.

Over time, this should translate into good economic news for these areas, as earlier Venture Forward research has shown that increases in the number of microbusinesses per 100 people leads to lower unemployment rates and a $195 additional increase in annual median household income gains – for all residents of a community, not just the microbusiness entrepreneurs.

This lower income group is creating a disproportionate number of microbusinesses despite facing long odds because of lack of access to capital and other challenges.This lower income group is creating a disproportionate number of microbusinesses despite facing challenges, such as difficulty getting bank loans and access to other types of capital and living with the impact of redlining and other factors that have limited the growth of generational wealth.

More than 60% of these businesses were started with less than $5,000, compared to 54% of business started by people who are not resource-constrained.

The increased microbusiness vitality in poorer neighborhoods was determined by comparing state-level ALICE poverty data with how those states ranked on the Microbusiness Activity Index, a benchmarking tool created in partnership with UCLA Anderson Forecast in 2021 by Venture Forward. The MAI is composed of 14 data signals including the number of microbusiness entrepreneurs with active websites in an area, the sophistication of those websites, and the availability of broadband and other infrastructure needed for these businesses to thrive.

Entrepreneurs out of necessity

The increased entrepreneurial activity among poor and lower-income Americans is not surprising. A Venture Forward analysis from early 2021 showed that many Americans used their COVID-19 stimulus checks to start new businesses.

So who are these new microbusiness owners? The majority, 55%, are people of color, who make up 42% of the U.S. population. This echoes earlier findings that Black Americans, who face higher poverty rates than the overall population, have been starting businesses at a fast clip since the pandemic began.

The respondents to Venture Forward research reported facing many of the same obstacles BIPOC entrepreneurs have faced over the years. Nearly 40% said they had trouble raising capital, compared to 25% for wealthier respondents.

“We refer to these folks as underinvested entrepreneurs,” says Michelle Geiss, founder of Impact Hub Baltimore, a nonprofit social enterprise dedicated to helping low-income business owners. “They’ve faced structural obstacles like red-lining, and more generally have been left out of the networks where a lot of the resources and connections exist.”

Despite these challenges, the Venture Forward data suggests that this rising cadre of entrepreneurs is particularly resourceful and determined. Nearly 80% offer e-commerce functionality on their websites, compared to 63% for the rest. And while around 40% of all founders say their microbusiness is now a source of supplemental income, 87% want to turn it into their main source, compared to 68% of those safely above the poverty line.

What can policy-makers do to help?

Microbusiness owners tend to be a self-reliant group, in part because they don’t know where to find help and don’t have the time to look for it. Two-thirds say they aren’t aware that any government assistance programs exist. But when made aware, economically-struggling owners are more receptive to making the most of the help, as evidenced by their participation in almost every type of program mentioned in the survey, including those offering subsidized rent, grants and other forms of capital, and help with digital marketing.

Geiss, who co-founded Impact Hub Baltimore ten years ago, says there’s an even more powerful way for local governments and NGOs to help: building a community of committed entrepreneurs with the experience, talent and resources to help each other succeed.

Here’s why.

Q: Baltimore is something of a microbusiness success story. Tell us about it.

Our microbusiness density is three times the national average. We feature that statistic from Venture Forward on our website, and make a point of sharing it on the first day of our six-week Empower Baltimore program to help local businesses boost their digital presence. We want people to know that our city is unique – that we’ve got a lot of people with hustle, who are making things happen.

Q: Were you surprised by Venture Forward research showing that communities with more people below the poverty line have more microbusinesses?

First of all, I want to point out that people can move in and out of poverty. It’s an economic threshold, not an identity. If people have success with their business, it may offer them a pathway towards greater economic stability and growth than they were finding with traditional employment.

Q: You’re a microbusiness owner yourself. Why did you start Impact Hub Baltimore?

We opened in 2015 to support the growth of social enterprises in the city, people who were focused on education, health, equity, and the arts. But when the pandemic hit, we could see that all small businesses would face many of the same problems. So we’ve been part of multiple initiatives to try to help everyone keep their doors open.

Q: What are the unique problems that less affluent microbusiness owners face?

Besides underinvestment, redlining, and lack of generational wealth, these business owners usually work on their own, or maybe have a couple of people on the team. They’re not going to know how to do everything that a business requires. Plus, they may need to succeed to put food on the table. The stakes are so high, but where do they find good, trustworthy advice?

Q: How did GoDaddy’s Empower program help?

GoDaddy came to us, I think because we could be a connector to other people and organizations in Baltimore. When we heard the Venture Forward data about the power of getting businesses online, it really resonated. I’ve known so many entrepreneurs who rely totally on social media but don’t have a website. It was difficult to see how people could grow beyond their immediate network without a better ability to be found online. So we spread the word, and ended up collaborating with 18 other organizations who could then reach into their networks.

Q: What advice do you have for advocates who are trying to help under-invested entrepreneurs in other cities?

Make you sure you look for participants who are committed to their neighborhoods and even to the other businesspeople in the community. There’s a lot of power in that. Collaboration unlocks more potential than if everyone is always competing with each other, especially in these underinvested communities. Yes, business is competitive, but we like to see entrepreneurs who are willing to make that introduction or offer advice to someone else.

Q: How do you know when it’s working?

I was just talking with a colleague about how incredible our attendance numbers are for our Empower program. Almost everyone that signs up attends every session and finishes the course. That’s pretty rare, actually. We think it may have something to do with a sense of accountability, because of who we chose. It’s like a self-reinforcing pattern: they benefited from someone investing time in them, so they want to invest in the next person.

Q: What do you think of the Venture Forward data?

It’s really powerful, because it shows that lots and lots of very small businesses can be a significant economic engine for a city. And these folks don’t have advocates. Nobody from a one-person shop is hiring lobbyists to go to Annapolis to push policies for them.

It might feel like small, incremental change, which is why so much economic development policy is focused on getting large companies to move into our cities. So all of people’s time and our tax dollars go into this, and it doesn’t keep the dollars local. Local entrepreneurs stay where they are. They’re from here, they hire people here, they grow here. If we can change the flow of resources so microbusinesses have access to the supports that large companies are able to lobby for, I think that we would actually see a change in the pattern.