5 Higher-Ed Programs Using XR to Transform How College Students Learn

Colleges and universities are using virtual and augmented reality in courses that range from human anatomy to media as a way to make education more immersive and inclusive.

By Stephanie Walden

Instead of reaching for scalpels, medical school students at Colorado State University’s Clapp Lab reach for virtual reality (VR) headsets, which dangle from the ceiling of the 2,500 square foot facility. Once students don their devices — each of which is connected to a high-powered HP workstation — they begin the day’s “patient examinations.”

Dissecting entire human cadavers in VR allows students to zoom into and explore body parts on a cellular level. “It’s a much more efficient and intuitive way to display and learn from this type of data,” says Tod Clapp, associate professor of biomedical sciences and the director of human anatomy at CSU. In internal surveys, 87% of students who have taken CSU’s distance anatomy class say VR has helped them understand spatial relationships better than traditional two-dimensional resources. Spatial cognition is particularly crucial in medicine, helping doctors understand everything from where a patient’s organs are located to how anatomical structures are connected.

According to Inside Higher Ed, the last five years have seen a “significant increase” in educational institutions using XR — “extended reality,” a term that encompasses both virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR). Studies conducted by Educause, a nonprofit that advances higher education via information technology, suggest that XR promotes engagement, exposes students to new and impactful content, and deepens their interactions with complex concepts.

HP is a long-time advocate of bringing XR technologies into higher-ed environments, partnering with Educause in their Campus of the Future program, which identifies use cases for XR in college and university classrooms. In 2017, HP also launched the HP Applied Research Network, an initiative that helps more than 20 educational institutions implement XR technologies. HP is one of the sponsors of Educause’s upcoming annual conference, to be held in-person in Philadelphia and online October 26-29.

“Concepts that are difficult to master in a ‘flat’ world — out of a book or looking at a chalkboard — are often much better suited for a 3D approach,” says Paul Martin, HP distinguished technologist emeritus, who spent 36 years at the company before retiring this year. “XR is going to be crucial for future educational experiences.”

Distance learning in VR

On top of helping students wrap their heads around complex concepts, the pandemic highlighted another practical use case for XR: giving homebound students an immersive, engaging experience, even when they can’t be in the classroom.

When the CSU campus closed in March 2020, the Clapp Lab purchased 125 HP laptops and shipped them, along with VR headsets, to students. They’ve kept this technology on hand and deployed it for home use as classrooms have reopened.

RELATED: Get a behind-the-scenes look at how today’s most intelligent VR solution came to be.

Clapp and other educators at CSU are now working on initiatives to bring this type of learning to underserved students and those who live in rural areas or have trouble commuting to campus.

“VR makes distance irrelevant — you can have access to experts from anywhere, and you feel like you’re talking to them face to face,” says Clapp.

Building community and critical thinking skills

In-person learning also benefits from advanced VR capabilities. At Florida International University (FIU), incoming students learn strategies to forge connections and adapt to new environments in a virtual experience called “COMMUNITY VR,” part of FIU’s First-Year Experience course.

Participating students enter a virtual, Everglades-style scene, only to immediately notice water rising around them. To avoid becoming completely submerged, small groups must work together to build structures out of blocks in VR. The exercise is designed to help students grasp the four “Cs” necessary to thrive in a university setting: creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication skills.

“The VR experience can provide an important analogy to the university experience itself,” says John Stuart, an associate dean for cultural and community engagement at FIU. In the same way as VR is an unfamiliar environment for many people, being on a university campus can be daunting for first-timers. Students have to work together and get creative to keep their heads above water.

Exploring XR storytelling

At the Johnny Carson Center for Emerging Media Arts at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, center director Megan Elliott helped craft a curriculum focused on how XR might impact the future of live theater and the stage, among other disciplines. Some courses, taught by computer science and emerging media arts professors, involve using motion-capture and body data from dancers as a way to control avatars, sound, lighting, and visual effects in a live performance.

When the pandemic struck, Carson Center faculty and students used virtual collaboration software Mozilla Hubs to move the coursework online, re-creating the Johnny Carson Center virtually in just two weeks.

Like Clapp, Elliott sees serious potential for XR as a way to connect students from around the globe — including historically excluded communities — to top-tier learning institutions and experiences.

“We’re really interested in our students becoming facile with both real-time creativity and real-time collaboration in virtual worlds,” she says.

Evaluating the influence of media in XR

At Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Public Communications, Associate Professor T. Makana Chock is conducting research on storytelling in XR.

“My research looks at the potential effects of extended reality,” she says. “How are people processing messages or information that they receive in XR? And what are the effects of that type of content on people's attitudes and beliefs?”

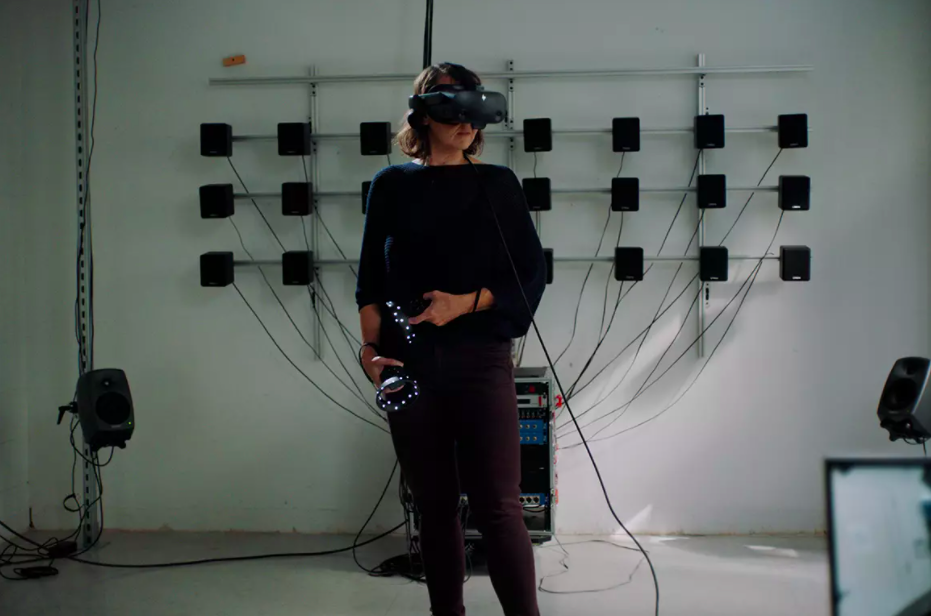

The ability to quantify some of these data points through biometric sensors, a feature of the HP Reverb G2 Omnicept devices that Chock uses in her research, could be a game changer. The devices capture data on eye movement, heart rate, and facial movements, allowing her to understand how people react to immersive experiences and design for new avenues of interactivity.

So far, Chock’s research has found that XR tends to create greater levels of presence and immersion among users. It also seems to heighten emotional responses, which in turn can lead to more pronounced changes in attitudes. But results are dependent upon a person’s own experiences and biases, Chock explains. And if content is too complex, it can result in cognitive overload or become emotionally overwhelming.

One major issue that needs to be addressed before XR can be widely used for social justice, Chock notes, is accessibility. “The pandemic created a greater awareness of the opportunities for the use of XR in education, but I think it also revealed some of the current limitations — some of which are technological and will be addressed in time, but others that are social, [like access and racial/gender equity],” she says.

Synthesizing a more inclusive future

At Columbia University’s Computer Music Center, the oldest electronic music research facility in the Western Hemisphere, those social issues are top of mind. The center houses one of the world’s largest collections of historical analog synthesizers and hosts classes like “Introduction to Digital Music,” “Sound: Foundations,” and “History and Practice of Electronic Music.” This last one is especially pertinent to access and racial equity.

“The history of experimental sound includes a great many women and people who are nonbinary or have non-White/male/hetero/cis backgrounds, but their stories tend to get buried,” says Suzanne Thorpe, a Mellon teaching fellow and lecturer at the Music Center.

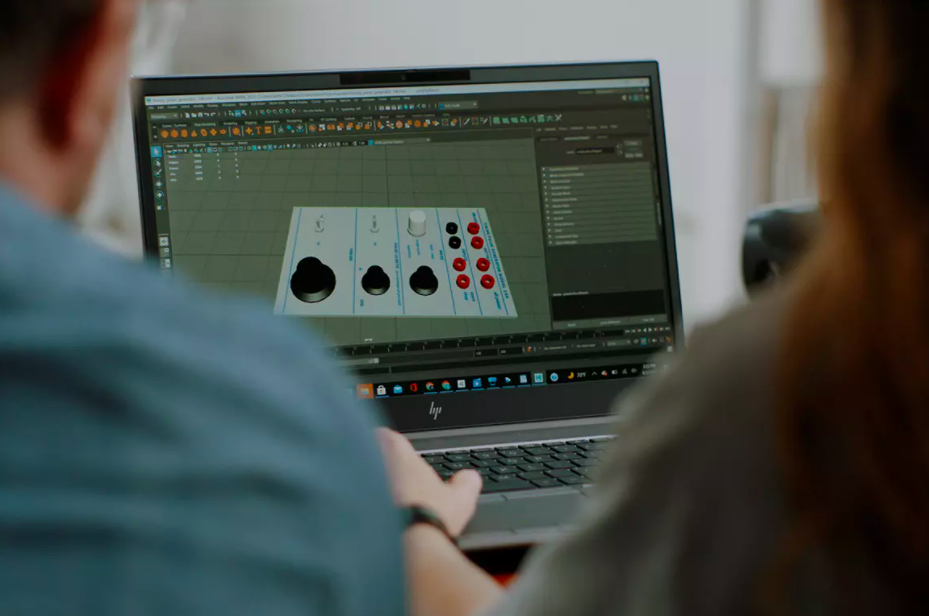

Seth Cluett, assistant director of Columbia’s Computer Music Center is leading an initiative to use VR and AR to give students an opportunity to play and record using the center’s synthesizers and devices without actually touching the vintage hardware, which can be intimidating to novices.

“What we've tried to emphasize is that there is no boundary; there's no difference,” says Cluett, referring to the difference between the virtual and physical experiences. “It is only understanding what kind of embodied physical gesture, action, or behavior you want to have control over a sonic result.”

They also use the data-capture abilities of the HP Omnicept headset to understand how students feel when they’re introduced to the historic collection. The HP Omnicept’s sensors provide insight into where students’ eyes go, for example, or what causes them stress, giving Cluett and Thorpe information they can use to design an experience that makes students feel more comfortable working with the physical devices.

“[We hope this work] might encourage those who feel hesitant because they’ve never seen ‘themselves’ represented, historically or culturally, in those kinds of environments,” Thorpe says.