Can Food Supply Chains Cope with COVID-19?

The complex global systems that bring food from fields to forks are overcoming many hurdles to keep us fed.

It’s a luxury easily taken for granted in the developed world – that we can expect diverse, healthy and safe food on our supermarket shelves. But this is only possible thanks to the complex global supply chains capable of rapidly and safely growing, processing, and transporting food by land, sea and air from fields around the world.

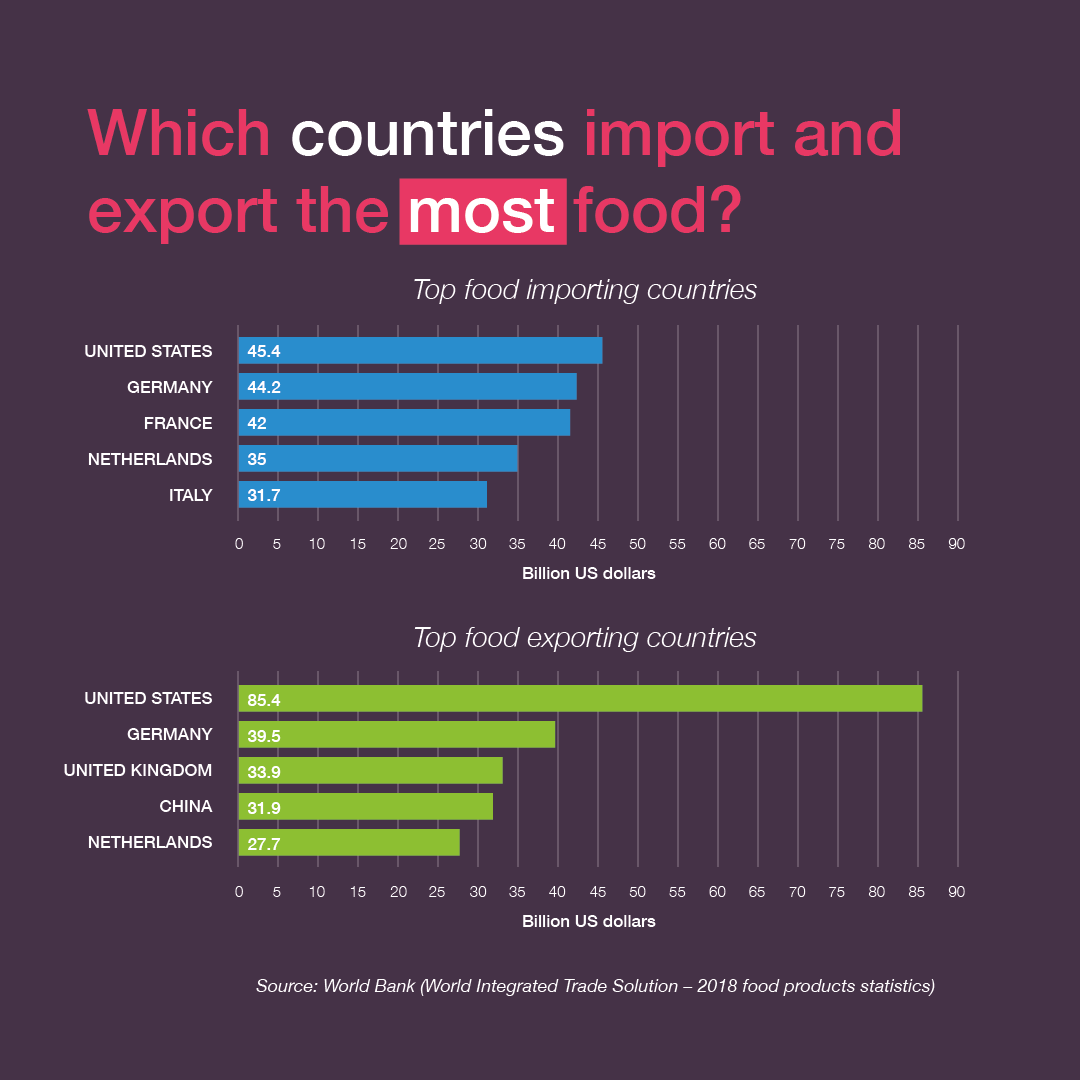

The scale of these systems is staggering. About 23% of the food globally produced is traded internationally, and countries worldwide import food at a value of approximately $1.5 trillion annually. It’s no surprise then that the global food system accounts for 10% of the world’s GDP and employs as many as 1.5 billion people.

However, as governments around the world take measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the food system faces extraordinary disruption. Social distancing measures, travel bans, border closures, restricted transport channels and the temporary shutdown of much of the food service industry are significant hurdles to overcome.

From farmers and field workers, to food processors and retailers, the global pandemic is causing problems at every stage of the supply chain. For now at least, many sectors in the developed world have shown enough flexibility to ensure the delivery of food to consumers by adapting to new conditions. But is this also the case in less developed parts of the world?

To understand the challenges the world faces, we spoke to leading experts on global food supply chains to ask: how are we preventing a health crisis from becoming a food crisis?

Where the World Gets its Fresh Food

The world’s population is dependent on global trade for access to fresh, healthy, safe food. The United States, for example, imports 32% of the fresh vegetables, 55% of the fresh fruit and 94% of the seafood it consumes every year.

In the EU, around 80 million tons of fresh fruit and vegetables are produced annually for the fresh markets, according to Freshfel, the European fresh produce association. Of that, more than 30 million tons is traded between member states, with an additional 5 million tons exported outside the union.

In total, the EU imports almost 93 million tons and exports 91 million tons of agrifood products each year.

Today, countries often specialize in producing certain types of food and rely on each other to secure produce that can’t be grown locally due to climate or is cheaper to grow elsewhere. This reliance has led to great variety in our diets.

A healthy diet implies a diversity of product. No matter where, you can’t eat only local produce.

- Phillippe Binard, General Delegate of Freshfel

But what do global food chains that deliver these products to our fridges look like?

Heike Axmann, Expertise leader in Supply Chain Development and Logistic Design of Fresh Food Chains - one of the applied research groups at Wageningen University and Research, provides an example using French beans. The chain starts with laborers picking the vegetables on multiple smallholder farms in Kenya. The beans are then transported, packaged, shipped by air freight, and eventually delivered to supermarkets across Europe.

But, she points out, supply chains can look very different to this. Most of world’s farmers are smallholders, often not connected to the global system or linked formally to markets. Their produce often reaches markets via much smaller, informal, local systems. Typically, smallholders sell their produce to middlemen who transport it to towns and cities to be sold at markets or wholesale to shops and restaurants.

When the Music Stops

Regardless of what the produce is, or to where in the world it’s moving, all food supply chains are dependent on a key component: people. It’s people who sow seeds and harvest vegetables, people who drive trucks and package food, and people who unload the shipping containers bringing food from across the ocean. A pandemic such as COVID-19 forces people to change how they work and how they eat, meaning there are multiple points of disruption that can ripple through supply chains in both directions.

“It’s like a dance in a historic movie,” says Nancy Tucker, Vice President, Global Business Development at Produce Marketing Association (PMA), a trade organization representing companies in the fresh produce and floral supply chain. “The dancers move from partner to partner down a chain, but if the music stops the dancers all pile up.”

She gives the example of Chilean cherries, 90% of which are normally shipped to China, where they are distributed around the country. When the cherries are unloaded, the containers are refilled with another product and then shipped to another country, where the cycle continues with the containers eventually making their way back to Chile to be used once again for cherries.

However, the onset of COVID-19 stopped the dance, causing the containers to pile up –initially in China, where stringent quarantine measures prevented workers from unloading and reloading containers. The number of containers leaving Shanghai dropped by 25% in February, which had a knock-on effect of causing record low levels of available containers in other ports around the world. With Brazilian coffee sellers and Canadian lentil exporters struggling to secure the containers needed, trade began to seize up.

To successfully tackle this challenge, cross-border collaboration and organization is paramount, and measures are being quickly implemented to keep produce on shelves. Binard points to the closing of the Austrian border with Italy as a success story where swift actions kept trade moving: “There were about 100 kilometers of traffic jams and, in less than 48 hours, arrangements had been made to set up ‘Green Lanes’ that allowed fresh produce deliveries through.”

Changing Consumer Demands Mean Supply Chains Have Had to Shift

Beyond transportation and logistics, one of the biggest challenges for food supply chains has been the immediate shift in consumer spending brought about by the temporary closing of virtually the entire food service industry, from school cafeterias to restaurants to canteens to hotels. It is a huge global market – worth an estimated $3.4 trillion in 2018 – so the sudden lack of demand has an enormous impact throughout the food supply chain.

In the U.S. and the EU, about one third of all fresh produce is delivered to the food service industry. The loss of this market has forced supply chains to quickly figure out how to shift their focus. This has presented a massive challenge.

The U.S. and other countries’ supply chains have become extremely efficient and extremely effective. Some growers target their produce specifically for food service. It meets exact specifications and is packaged in a precise way. But now that market is gone. It can be very difficult to change to a different market.

The U.S. and other countries’ supply chains have become extremely efficient and extremely effective.

Some growers target their produce specifically for food service. It meets exact specifications and is packaged in a preciseway. But now that market is gone. It can be very difficult to change to a different market.

- Nancy Tucker, Vice President, Global Business Development at Produce Marketing Association (PMA)

Organizations such as PMA are helping producers find new buyers or shift their process to meet different needs, but it is not as simple as delivering food to a grocery store instead of a restaurant. What consumers buy to cook at home differs from what they order when they are out and with restrictions on how often people can travel to supermarkets, they are more likely to buy canned goods with longer shelf-lives than fresh produce.

Added to this are uncertainties around the speed at which the different parts of the food service industry might be able to reopen and how the economic fallout from the crisis will affect consumer spending.

The Potential for Both Food Waste and Insecurity

Fresh fruit and vegetable products are particularly at risk to disruptions in supply chains, with perishable goods rotting and going to waste if left too long. Even before the pandemic, one-third of all the food produced around the world was lost or wasted before it was consumed, and COVID-19 is introducing new contributing factors.

“We expect an increase of food loss and waste around the world for a number of different reasons,” explains Axmann. “In Europe, for example, the main reason is a lack of labor and the sudden drop in the food service market.

“But we also expect higher losses and waste in developing countries because of border closures, trade bans, restrictions to sending products to markets, as well as the unavailability of labor at the right moment. There is the potential for a long-term increase in food insecurity.”

Smallholder farmers in developing regions and farm workers, often from economically difficult backgrounds, are bearing the brunt of these challenges. Reduced trade, the closure of village marketplaces and domestic travel restrictions pose a very real threat to their livelihoods. They also create the potential for a dire situation where food goes to waste while others go hungry.

Take rice for example. More than half of the earth’s population (3.5 billion) depends on rice as a staple to their diet. The pandemic has seen panic buying which in turn prompted rice-exporting countries to impose limits on exports leading to a jump in its price. In Thailand, rice prices rose by 15% in March to its highest level since July 2013. This hugely impacts poorer households, where rice can account for almost half of monthly spending.

Adapting to the Challenge but at a Cost

Crucially for the global fresh food supply, farmers, industries, organizations and authorities continue to rise to the challenge – from smallholders implementing social distancing and increased hygiene measures to the global coordination and cooperation that keeps the trade systems we depend on moving.

PreviousNext123Of the 80 million tons of fresh fruit and vegetables produced in the EU annually more than 30 million tons is traded between member states, with an additional 5 million tons exported outside the union.The number of shipping containers leaving Shanghai dropped by 25% in February, causing record low levels of available containers in ports around the world.Reduced trade, the closure of village marketplaces and domestic travel restrictions pose a very real threat to the livelihoods of smallholder farmers and farm workers in developing regions.

“There are a lot of new protocols that need to be put in place and that is challenging,” says Binard. “But the sector has demonstrated that it can organize to the specific pandemic.”

However, this comes at a substantial price. For growers and suppliers in Europe for example, Freshfel calculates an increase in costs of €1 billion in the first two months following the pandemic. This is largely the result of mass logistics disruptions, and increased workforce and operations costs through measures like supplying personal protective equipment.

“As the crisis continues, the question is how long can the sector continue to support this additional cost?” asks Binard. “Hopefully, if we move back to normal, there will be better rules and organization of workers that could decrease the cost.”

The needs of the industry will also change with the seasons. In the northern hemisphere the summer fruit picking-and-harvest season, for example, will demand new efforts to allow migrant laborers to travel across borders and to work safely in fields and packing houses.

The Road Ahead

There is hope that this turbulent period will result in more flexible and resilient supply chains that can better adapt to sudden changes in demand. These will be key to securely supplying the world with the food it will need in the future.

We cannot go back to local-only food chains. We are living in a global food system.

We must develop intelligent global food systems which are sustainable, circularand inclusive for smallholder farmers.

- Heike Axmann, Expertise leader in Supply Chain Development and Logistic Design of Fresh Food Chains

One solution to help achieve this is the greater use of technology and data. Tucker explains, “This pandemic is going to have long-term effects on every part of our world. There will be greater use of technology, such as robotics in picking products, warehouses and cold storage areas.

“There will also be increased data usage. We will be collecting more at every point to gather information as food goes through the supply chain. The more data we have, the more accurate models and better forecasting we can make.”

The panic buying that occurred in the early stages of the pandemic highlights how crucial a role data can play. By providing transparency on how much of a certain product is available and when it will be delivered, consumers are better informed and can remain more rational in their spending habits.

In the meantime, the industry continues to adapt, aware that further uncertainties lie ahead. But there is collective understanding for the need to build a better, more robust system that can benefit everyone. As Axmann says, “Due to COVID-19 we are going to rethink our current food systems. This offers opportunities for transitions, making our current systems more resilient and sustainable, and global systems more intelligent. To make this happen, strong and effective collaborations between academia and the private and public sectors are needed.”